5 Insights Into Louis Kahn, Kimbell Architect

ArtandSeek.net March 31, 2017 47

Ever wonder what makes a building a work of art? A visit to the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth can help you answer that question.

- Listen to the whole conversation on Think’s podcast.

- “Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture” is on through June 25 at the Kimbell.

The late architect Louis Kahn designed the building, which opened in 1972. It’s widely considered one of his best works. The Kimbell has just opened an exhibition about Kahn, with drawings, models of his buildings, video and lots of insight into this complicated man. And there’s a new book out about Kahn. Think Host Krys Boyd recently invited Wendy Lesser, author of “You Say Yes to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn,” into the studio to talk about Kahn’s life and legacy.

Here are five highlights from Boyd’s conversation with Lesser. (Lesser often refers to Kahn as “Lou” for brevity.) Enjoy, and consider taking a trip to the Kimbell to see it person.

On Kahn’s Childhood Before He Moved To U.S.

Louis Kahn, Percé, Gaspé, Quebec, 1937, tempera on paper Collection of Sue Ann Kahn and courtesy of Lori Bookstein Fine Art

“His earliest, childhood memory, which he said was about when he was 2, was of drawing with his finger on a frozen window-pane. He remembered the muddy streets of his village which was on this island off the coast of Estonia. He had memories of the castle that was there, which is a huge 14th century fortress and castle. And I think he probably carried a lot of memories in ways that were not fully conscious. For instance, what it’s like to be in a country where light and dark are so extremely separated as they are in those long evenings of a Baltic summer or the very short days of a Baltic winter. And he had a life long affection for places by the sea and a way of designing work that faced out to the sea, that I think might have come from his island childhood.”

Jewish Community Center, Ewing Township (near Trenton), New Jersey, Louis Kahn, 1954–59 Exterior view of the Bath House with a wall drawing at the entrance designed by Kahn © Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, photo: John Ebstel

On What Say Yes To Brick Means

“So it comes from a phrase, a little anecdote that Lou often used, either in classrooms or when he was giving public speeches and I’ll recite the little anecdote and explain why I chose it for the title. The anecdote goes like this:

‘You say to brick, what do you want brick? And brick says, I like an arch. And then you say to brick, well arches are expensive and I can put a concrete lintel over the the space, what do you think of that brick? And brick says- I like an arch.’

So I loved that story because it tells how much he cared about his materials, that he viewed them as almost living things speaking back to him and he payed attention to their qualities and did in a way, what they told him to do. But also because Lou himself was like that. Louis Kahn was a very assertive resistant person, who didn’t seem that way on the surface. He seemed affable and self-mocking and friendly but when he wanted something to be a certain way, he made it that way and other people couldn’t talk him out of it. So he was like the brick in that way. “

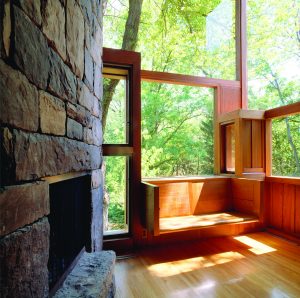

On How His Use of Light Was Not Accidental

“Light was one of his building materials. Not that he has a sentence of his notebook that says that, but that it’s so clear when you go to his buildings that he’s thinking all the time about how light functions- natural light. And it wasn’t the way other people were building at that time. So he had to be thinking about it and doing it on purpose and he had to be creating those openings in walls and in ceilings that would allow that to happen.”

Fisher House Window Seat, Norman and Doris Fisher House, Harboro, Pennsylvania, Louis Kahn, 1960–67 Photo by William Whitaker, July 2011

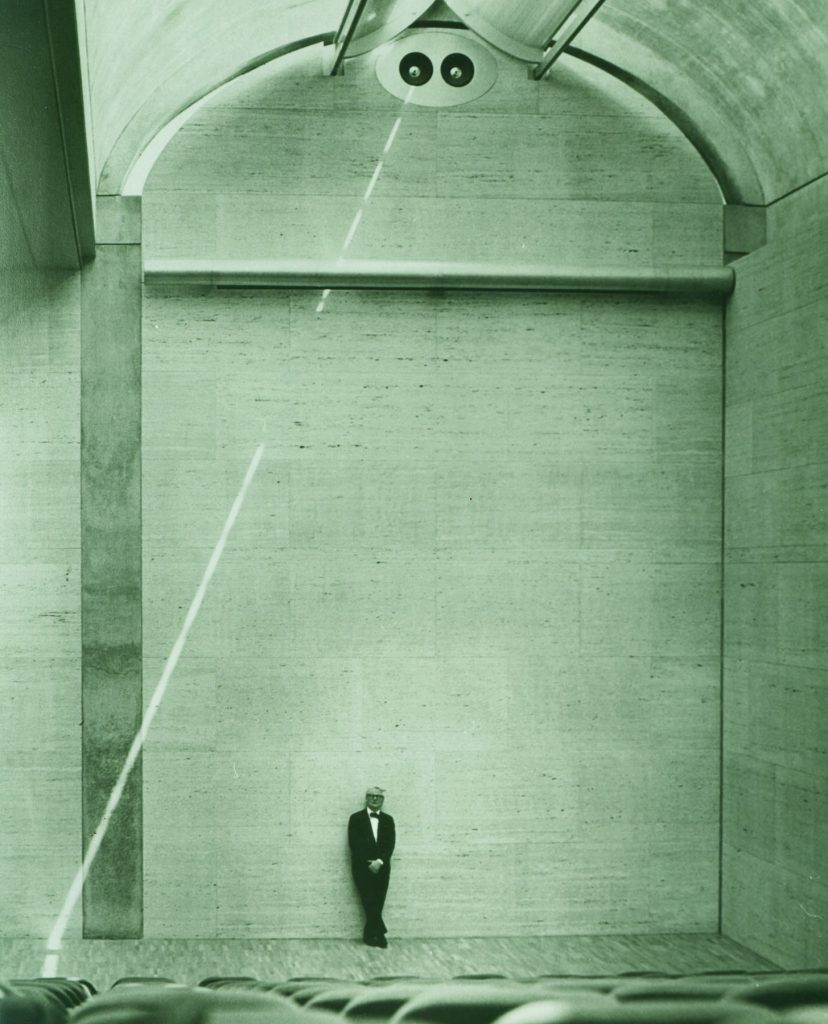

On Why The Best Way To Experience The Kimbell Is During The Day

“It’s a perfectly beautiful museum at night and has its own virtues. But luckily for us, it’s mostly open in the day. And the quality of light at the Kimbell is unlike anything I’ve ever seen in any other building. Even in other Louis Kahn buildings. There are great lighting effects in the Dhaka parliament, the National Assembly Building in Bangladesh, and wonderful lighting effects at the Kimbell Museum, and even in a less featured building of his, the Rochester Church, the First Unitarian church in Rochester. All of those buildings have great use of light and so do many others. But the Kimbell is really special. The way that light diffuses through the ceiling, and it kind of shimmers along the concrete curve that’s above your head, and you can’t quite figure out what’s creating that glow- is just amazing.”

Louis Kahn in the auditorium of the Kimbell Art Museum, 1972 © Kimbell Art Museum, photo: Bob Wharton

On Why Moving Through A Kahn Building Is Special

“I think you are very aware of your own body as he was- I mean he was interested in sports and athletics and love affairs, all types of things that use the body. And he had a very strong physical sense of himself and he transmits that to you in the building. So you don’t feel dwarfed in any way, even though there are often these huge high ceiling way above your head- that make you feel, I think I say in the book, crowned almost.

All this empty space above your head is elevating you, not making you tiny and ant-like. That’s just the amount of space you feel around you. And then the beautiful light makes you feel as if somebody has shaped reality in a way that makes it even more pleasing than it would be if it was just natural. There’s a sense of human involvement making nature more beautiful than it was, making materials more beautiful than they were. And utility blending with beauty, utility becoming beauty his really what happens in his work.”