All Those Murals You’ve Been Seeing? They’re Not Just In Deep Ellum

ArtandSeek.net October 16, 2019 29If you’re in Oak Cliff, Deep Ellum, along lower Greenville, you often see large-scale, eye-catching wall art – murals that can lend a place some artsy-urban atmosphere. Next Thursday’s State of the Arts public panel presented by Art&Seek at the Dallas Museum of Art features three Dallas muralists. KERA’s Anne Bothwell asks panel moderator Jerome Weeks, so – what’s up with all these artists going big?

Jerome, why murals? Or more to the point, why murals in Dallas – now?

Because Dallas is getting covered with them – now more than ever. This is Frank Campagna, often called the godfather of Deep Ellum because he opened one of the first punk clubs there and because he’s been painting murals in that neighborhood since the late ‘80s. He and real estate developer Scott Rohrman, the guy behind the 42 Murals project, are really responsible for giving Deep Ellum some of its artsy-gritty, urban look, a look that even massive new developments like the Case Building apartment towers are acknowledging.

“When I started doing murals,” Campagna says, “it wasn’t really an acceptable art form, so there was a lot of ground to break. And now it’s completely acceptable and everyone wants one and their mother wants one.”

Jeremy Biggers‘ portrait of Selena in Oak Cliff.

Of course, graffiti won that whole ‘is it art or is it vandalism?’ war a couple decades ago. But when I say Dallas is getting painted these days, I think people may have in their heads a couple of big, familiar images – like Frank’s famous Deep Ellum TV set on Good-Latimer or artist Jeremy Biggers’ giant Selena in Oak Cliff. But when I drove out over the course of two afternoons recently, just an hour or so each day, I went to capture a few of the notable murals I wanted to highlight during next Thursday’s panel discussion.

And I came back with more than 70 photos – from West Dallas, Fair Park, Bishop Arts, the Cedars, lower Greenville, Deep Ellum —

And that’s really just sort of downtown and the immediate vicinity.

Right. I wasn’t trying for anything comprehensive, some encyclopedic survey. But one reason I didn’t venture any further north than lower Greenville or further east than Fair Park was simply I had so many images already.

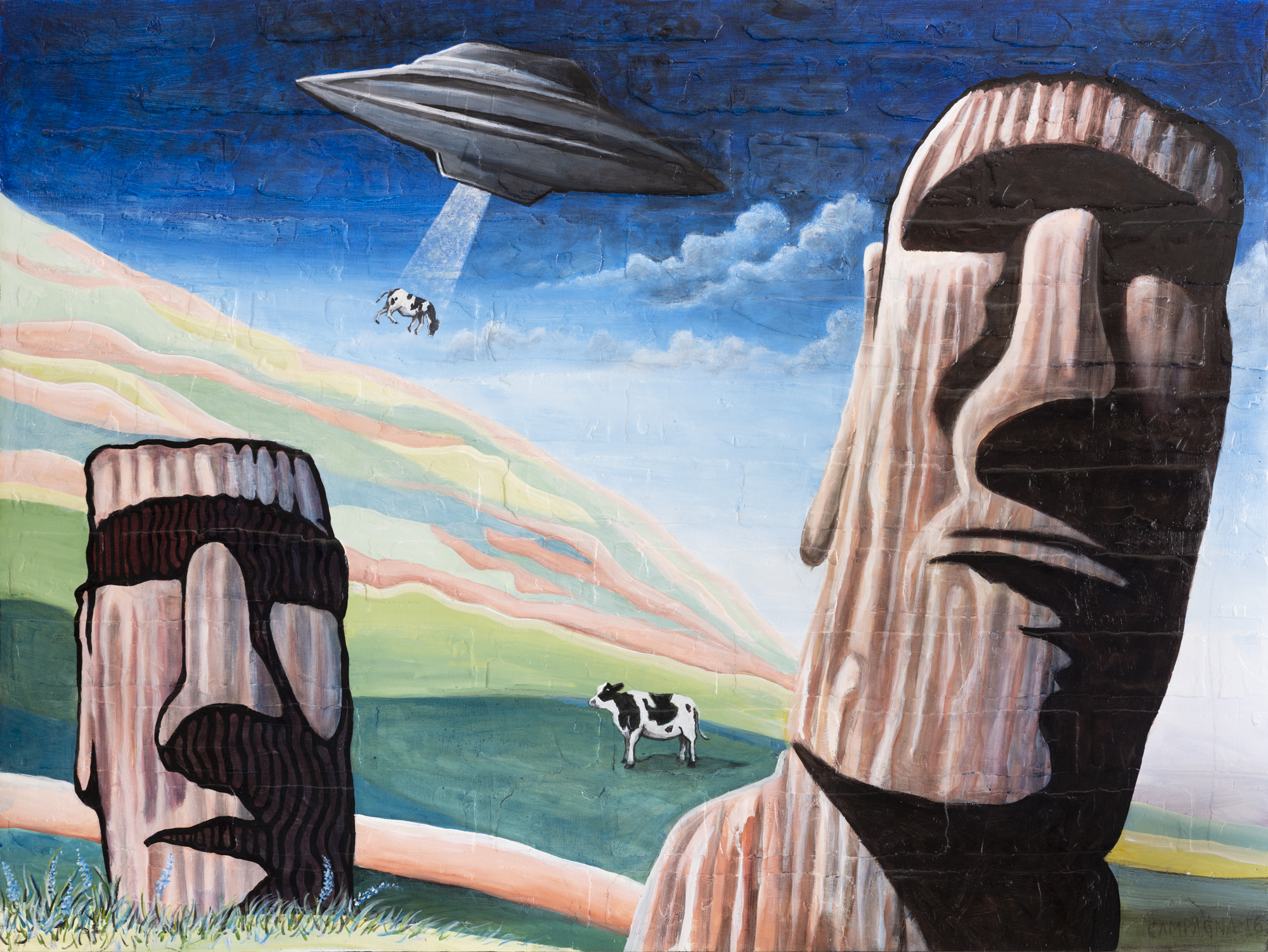

Frank Campagna‘s Easter Island mural in Deep Ellum.

But again, why so many now?

A couple of reasons. One, developers and storeowners – especially if they’re in a booming, walkable area like Bishop Arts — they know murals can announce their presence. Hey, we’ve arrived! This is new! We’re part of the neighborhood. Plus, they’re a relatively inexpensive way to do that, to change a person’s commute. “Look at that, that wasn’t there yesterday.”

And murals are not like billboards, really. Many see the two as basically the same thing: a big, often commercial image. But murals are typically ground-level, so they’re more Instagram-friendly, another way you get your shop or your condo project noticed.

But they’re also more artsy and funky-urban than the average billboard. You don’t see murals so often in suburban, gated communities or along Kroger strip centers. It’s no surprise, then, that in Dallas, graffiti and murals have tended to flourish in older sections of the city like Deep Ellum, Oak Cliff or West Dallas, places with brick walls and warehouses. In European cities, murals are often everywhere for a reason: So much of those cities have been made of brick and plaster for centuries. In America, our gleaming downtowns are mostly steel and glass. Not much use trying to paint on that. So even as our older city areas get duded up with new boutiques, pho restaurants and luxury apartments no one can afford, they often get a coat of paint from one of the most ancient arts we have — painted walls — and that paradoxically, lends them a trendy-yet-old-school look.

Sam’s Club on lower Greenville has a sizable mural along one side by Dallas artist Michael McPheeters. Photo: Jerome Weeks

Is this just about commercial demand – developers wanting to add a little urban cachet to their projects?

That’s part of it. But there’s also younger artists who’ve developed their chops, developed a style, and now they want to take that to a bigger scale. And murals are like architecture – they’re an art form that can’t really be ignored. They’re not stuck away in galleries. They’re public experiences. Everyone sees them. Jeremy Biggers paints typical, gallery-sized canvases, but in 2015, he decided to go big.

“Working in a public space was always a dream of mine,” Biggers says, “so being able to see my work even larger and being able to work in public spaces was something I always wanted to do, to give back to kids that were like me.”

What does he mean ‘give back to kids that were like me’?

African-American kids in neighborhoods where the only public art might be billboards. So each year, Biggers donates one mural – because he sees these kinds of super-sized paintings as an ‘outdoor art gallery.’

Artist Pixel Pancho’s 15-story-tall trellis of vines and flowers on the Case Building’s twin luxury apartment towers in Deep Ellum. Photo: Jerome Weeks

Some of these newer murals – they’re tall, like the whole sides of buildings. And you know this means we’re not talking about a couple of teenagers doing this with spray cans.

That entire image of guerilla graffiti artists tagging subway cars still exists in people’s heads. And to a degree, those street styles exist in real life. In fact, there’s a block-long wall on the side of Deep Ellum Self Storage that I call ‘The Sistine Chapel of Dallas Grafitti Art’ – some 20 muralists are represented there with some amazing script work. The whole project was arranged by artist Ray Alvarez. You can see the video I took of the wall up above.

But it’s also true that Frank Campagna says, many of the painters he shows in his Kettle Gallery in Deep Ellum — they’re also graffiti artists.

But about those super-tall murals you mentioned, an internationally famous, Italian street artist named Pixel Pancho just covered fifteen stories of the Case Building, the twin luxury apartment towers in Deep Ellum with painted vines and flowers. That’s pretty mild work for him, actually. His murals are normally much more surreal, even macabre. Pixel Pancho works all over the world — his closest work to us before this was a large-scale painting of two mechanical cats for the Houston Mural Festival.

West Dallas dog bath – ‘All Dogs Go To Heaven.’ Photo: Jerome Weeks

But obviously, a project like that requires months of planning over safety and budgets and code restrictions. Even a typical two-story mural can require a great deal of effort: The site’s not level, so you can’t use a scissor lift or ladders, you have to rent scaffolding. You want to work during the day, if you can, when the wall’s in shadow and you’re out of the sun. Jeremy Biggers recalls painting one mural in Austin — and an hour later, it was gone because the building owner hadn’t gotten the right permits.

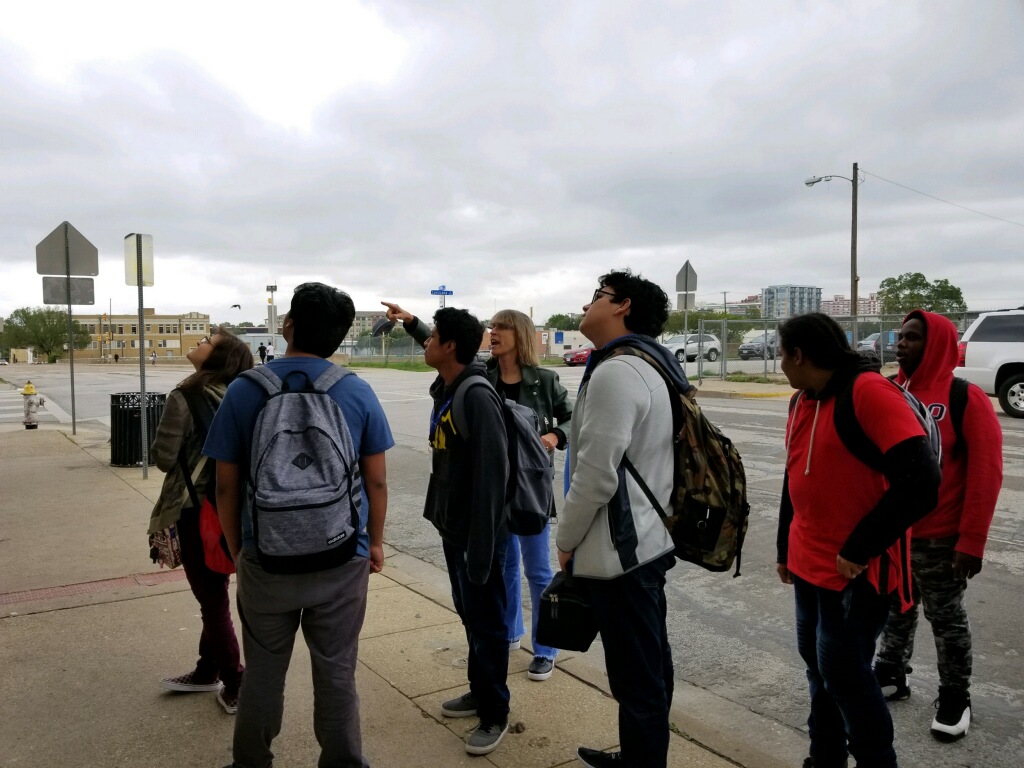

In fact, you also talked to Janeil Engelstad, and she is talking to high school students about how to paint this kind of large-scale public art project.

Engelstad and her arts group, MAP, Make Art with Purpose, collaborated with CityLab, the downtown DISD high school. And the school building is pretty drab, it’s in that area south of City Hall, north of the Mixmaster – parking lots and low-slung warehouses mostly.

Janeil Engelstad (pointing) and her class outside the DISD CityLab High School in downtown Dallas, planning a wall mural to spruce up the building.

And the students there want to be architects, urban planners, designers. So the idea was to spruce up the CityLab building. So the class went through the whole process, canvassing the neighborhood, researching not only city regulations but DISD regs. Looking into the purpose and history of signs and murals. And the students had to come up with their own complete design proposals.

Here’s Janeil talking about starting from square one: “When they thought of mural, they’re thinking graffiti or tagging, and public art, they’re thinking about, like, sculpture and the more traditional kind of arts, so they really gained a deep understanding of the history that murals have played socially and politically. For sure, they learned how monumental it is to create a large-scale public art piece.”

And did one of the student’s proposals actually get picked?

Fingers crossed – they’ll start painting that winning proposal this November.

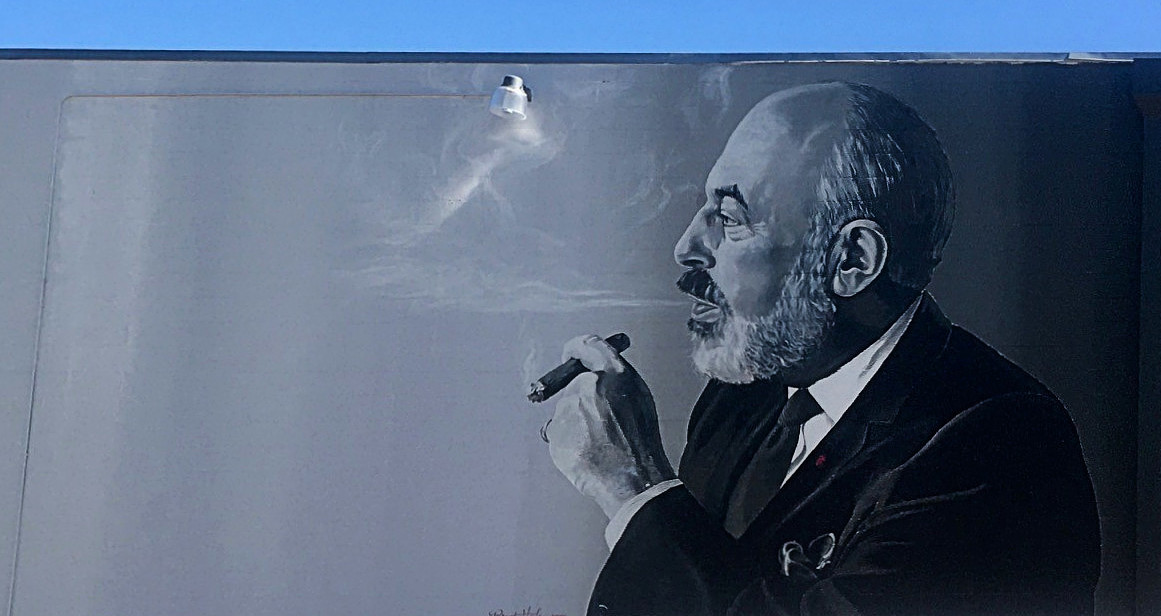

Artist Brent Hale’s mural of Stanley Marcus in The Cedars. Photo: Jerome Weeks