Channeling The Strength Of The Women Who Lifted Him Up

ArtandSeek.net November 16, 2018 38Strength and pain, endurance and innocence, all radiate from the women in Tyrone Geter‘s charcoal drawings. They’re featured in the exhibition “I Come As One, But Stand as 10,000,” at the Patterson Appleton Art Center in Denton. The work explores race, poverty and intolerance around the world. In this week’s State of the Arts, I spoke with the South Carolina artist and retired art educator. He tells me that women – from his family in the deep south, to his late wife’s people in West Africa – have always been his source of inspiration – and support.

You can click above to listen to our conversation, which aired on KERA FM. Or read a transcript below.

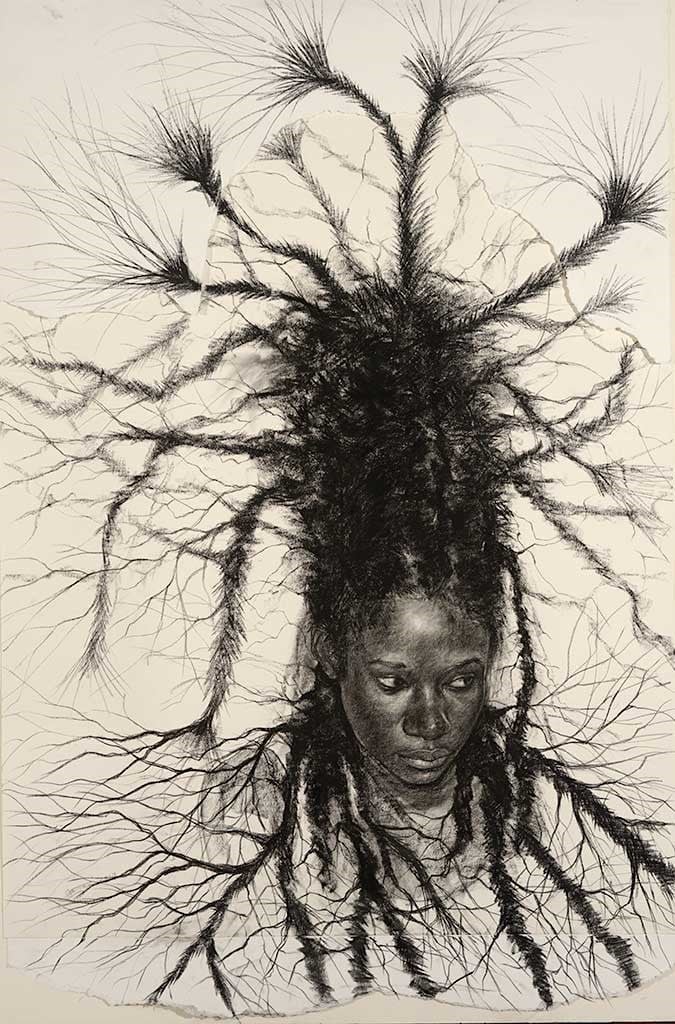

“Sting Like A Bee,” by Tyrone Geter

These are primarily large charcoal drawings of women and they look like real people but they have a mystical quality and their hair is fantastical, it’s like a huge collection of tiny tree branches.

Everybody wants to know about the hair.

When I was growing up in Alabama, women would wash their children’s hair and they would release them. They’d go outside and they’d play. There was never any concern about what their hair looked like. So years and years later, I was in Africa – the same thing. Children would wash their hair, go outside, they’d play, their hair’s out of place, they’re not going to say anything about it.

When we finally came back from West Africa – I have two daughters of my own – and one day my daughter said, “Dad let me just wash my hair, I’m going to go out and ride my bikes. It’ll dry faster.’ She went outside and didn’t tie anything over it. And the kids in the neighborhood just harassed her fiercely. It was terrible, because she never did it again. And it was like a sudden loss of innocence.

So years later, again, I was sitting and I was thinking about that. And I wanted to do something like that, so I could play down this thing of you have to have your hair straightened or braided or whatever. It’s however you chose to wear it. And it is the inside of a person we should be looking at.

Plus, when you see it looking more and more like a tree branch, that’s also pushing that connection to nature, which is one of the things I saw when I living in West Africa. That close tie to nature that everybody seemed to have. That was part of that, because it comes from great strength.

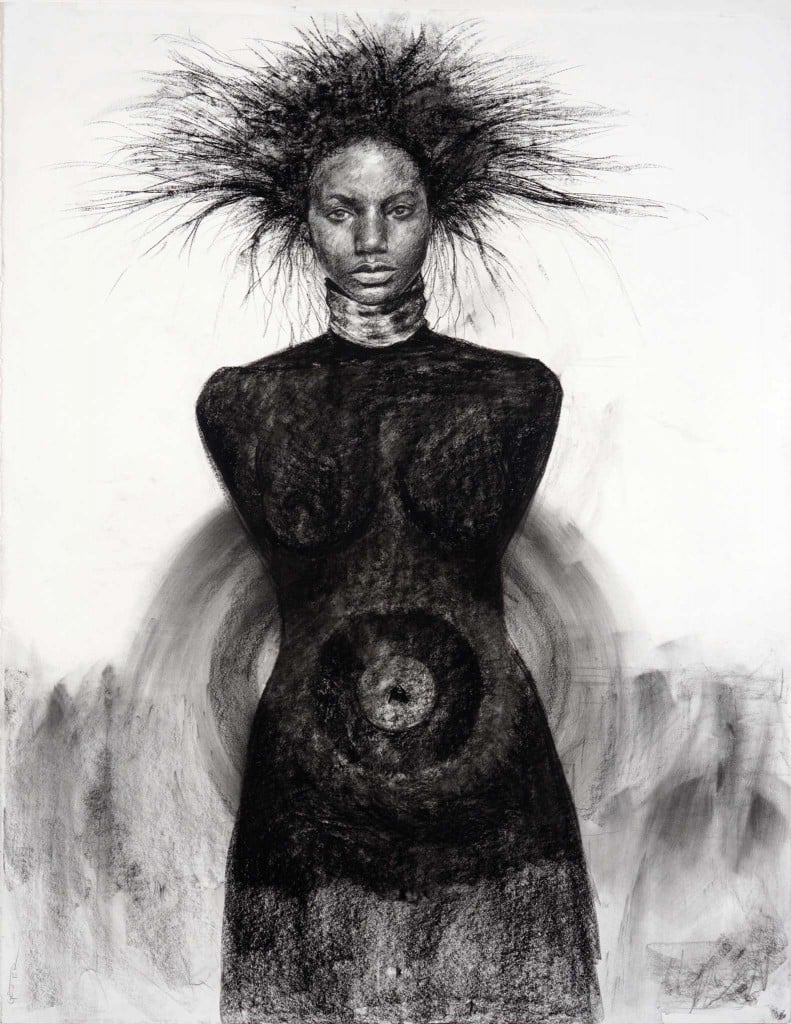

“Bull’s Eye,” by Tyrone Geter

Your mother was one of 10 children from a family of former sharecroppers. She left grade school and endured a lot of hardship, including racism in the Deep South. You credit your mom and other women in your community as inspiration. How is that translated in your work?

I look at what my mother went through just to get me to where I am now. She had a third grade education. They were from Georgia and when they came to Alabama, they worked mainly as domestic workers.

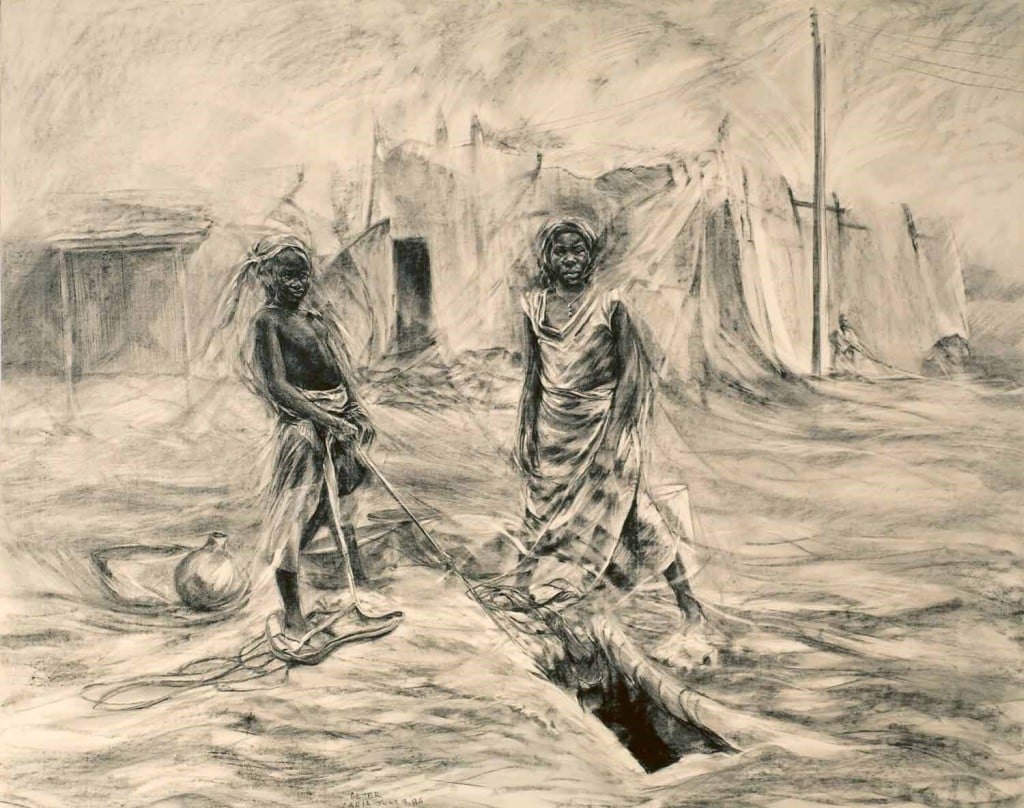

“Water, Water, Always Water,” by Tyrone Geter.

My mother, she left Alabama and went north. She worked for this lady about, must have been around 10 years or so, and finally, when I got ready to go to college, she went to the lady and just told her, “I want you to give my son one year of college. He wants to go to college.” And the lady said first, “Well, that’s kind of expensive.” And [my mother] told her, “You haven’t paid any income tax on me, no federal, no nothing, ever since I’ve been working here. So all I’m asking is just one year.”

So finally the lady agreed and that’s how I got to college. And that taught me even another level of respect. That my mother planned this. She planned this, over all of these years, that somehow, her son was going to go to college.

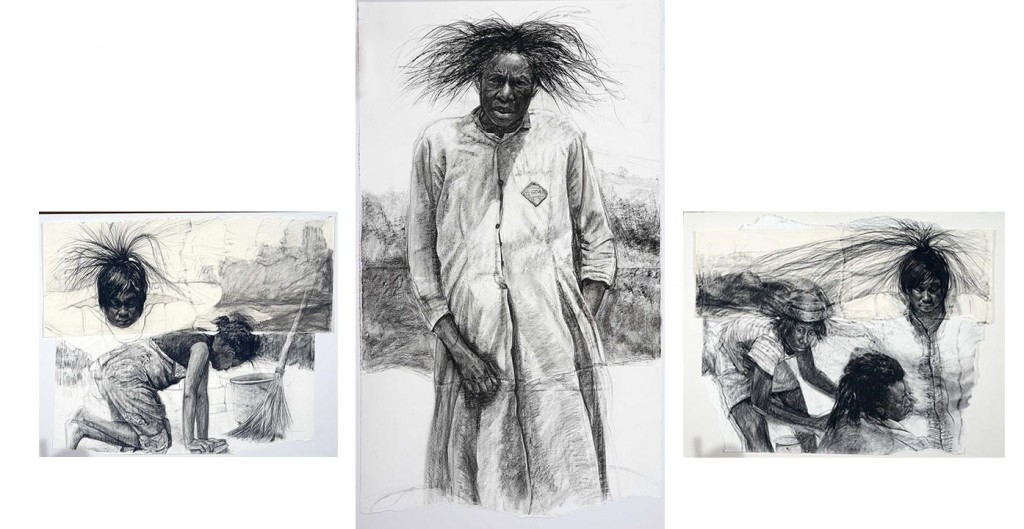

“Mother Nature’s Last In-House Domestic Servant,” by Tyrone Geter.

Women feature so prominently in your work. Can you explain why that is?

The role they played in my life has been really profound. I’ve never had a father. I had stepfathers around me, but they were not good people. But I’ve never had a father figure to look up to. So I’ve always looked up to the women in my life. They just don’t let me down.

My mother trusted me to do this art, the first time she saw me draw something. She always made time for me to do it and when I got discouraged, she’d say, “Oh, boy you’re going to be OK. You just keep at it, you have to keep working at it.” My sisters are the same way. They all promoted me, every second they got. My wife, everybody.

And when I do the work, it’s meant to not just to say thank you. It’s meant to draw that thing from them that was so profound. If I can get that into my work, maybe it could help. Maybe it can change things, you know?

“Wired,” by Tyrone Geter