Dallas To Memorialize Lynching Victims With New Public Artwork

ArtandSeek.net January 16, 2020 23In Martyr’s Park, a spread of grass, shrubs and a few trees are all that remain to memorialize the lynching of three slaves for whom the park is named. The city plans to change this with the new Memorial for Victims of Racial Violence that will be placed in the park.

The City of Dallas’ Office of Arts and Culture has put out a call for artwork to memorialize victims of lynching in the city. Kay Kallos, public art program manager, said the new public art project is part of an effort to continue dialogue about lynching and racial violence.

“It will bring attention to the specific lynchings that took place in the Dallas community,” Dr. George Keaton, founder and director of Remembering Black Dallas, said. “It would bring awareness and memorialization and reverence.”

The call for artists is open until January 26. Applicants can either access the application through a link on the city’s website or they can go directly to callforentry.org, an international database for public art. The application must include a letter of interest, resume, references, and portfolio.

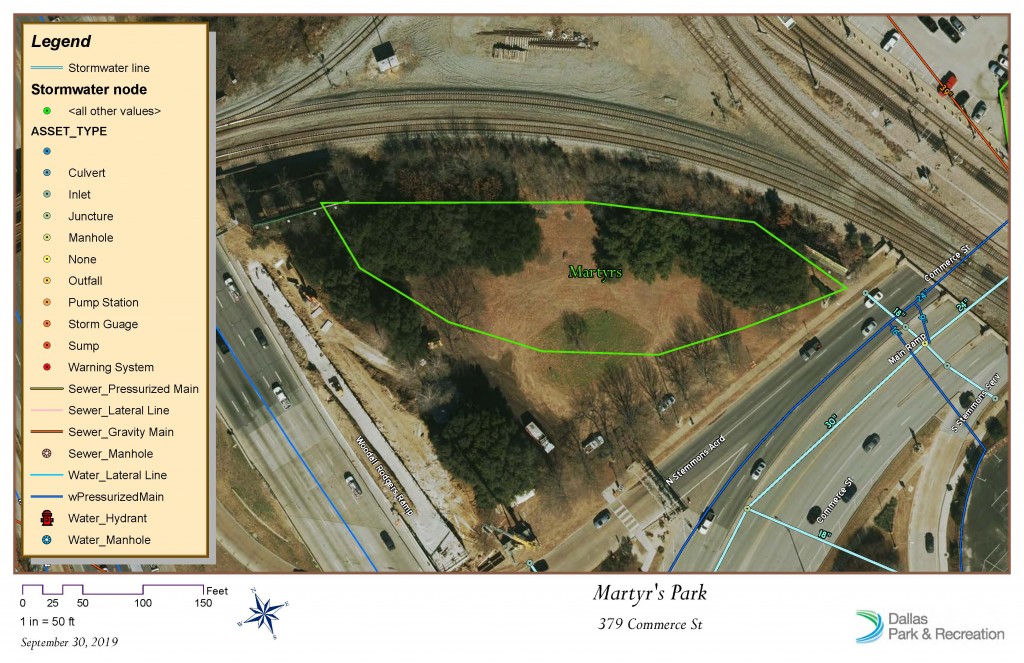

Area where the memorial will be located in Martyr’s Park. Image courtesy of Dallas’ Office of Arts and Culture.

Kallos said the city will begin narrowing down the applicant pool in February with selection panels consisting of the public art committee and advisory commission. In March, the city council will review recommendations from the panels and narrow the applicant pool in early May. She said the city expects to offer the selected artist an early summer contract. It’s estimated the actual construction of the memorial will take 12 to 18 months.

Kallos said the main criteria for the artwork is that it memorializes victims of lynching and that it is visible from a distance. There are no additional requirements regarding the artwork’s aesthetic or material. While the application is open internationally, Kalos said the city has a preference for hometown artists.

A Work in Progress

The idea for the memorial first came from an April 2018 briefing from the Mayor’s Task Force on Confederate Monuments. The memorial was initially dedicated to Allen Brooks, who was lynched in front of a crowd of 5,000 in downtown Dallas on March 3, 1910 — but the scope of the project quickly expanded as research revealed numerous other victims of lynching in Dallas.

“The working group really felt like a broader group needed to be recognized,” Kallos said.

In Texas, there were 493 lynchings from 1882-1968, according to the NAACP’s website. Research from the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, shows there were 3,595 “racial terror lynchings” from 1877-1950 in 12 Southern states including Texas.

Since December 2019, the city has hosted four community meetings to discuss the vision for the memorial.

“[The community’s] input indicates that they are very happy to see this topic addressed, that it is a very hopeful thing because it hasn’t really been talked about,” Kallos said.

She said the people who show up to these meetings are a diverse group who extend beyond the family members of the victims of racial violence — academics, former city council members, commissioners, artists and interested citizens have been in attendance. Organizations, including Friends of Fair Park, Dallas Truth, Racial Healing and Remember Black Dallas, have also collaborated on the project.

A Link Between Past and Present

Keaton of Remember Black Dallas said the legacy of lynching has continued in today’s society.

“The prison system has become a big business as far as profit — it’s another form of lynching in another matter,” he said. “When you have police officers who are shooting innocent people, it’s a form of killing. Because the bottom line is that you are killing a person unjustly…by definition, that’s the definition of lynching.”

Merriam-Webster defines lynching as “to put to death (as by hanging) by mob action without legal approval or permission.”

Keaton said he hopes the memorial will be a reverent reminder that lynchings happened on the ground we walk on everyday. He also hopes it will provide some healing to the community.

“The first hope is that it would be the first memorialization for these people who haven’t been given a second thought,” he said. “I hope it would give some closure to these unjust lynchings that took place and heal some wounds that have been opened. Even though it’s not my wound, it’s still part of my culture and heritage.”