Frank Lopez

ArtandSeek.net June 15, 2017 38Welcome to the Art&Seek Artist Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the personal journey of a different North Texas creative. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

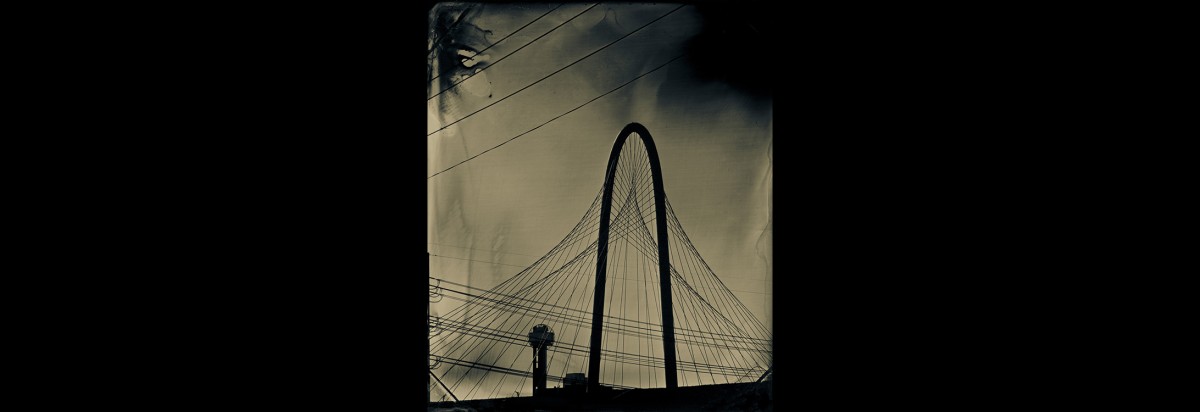

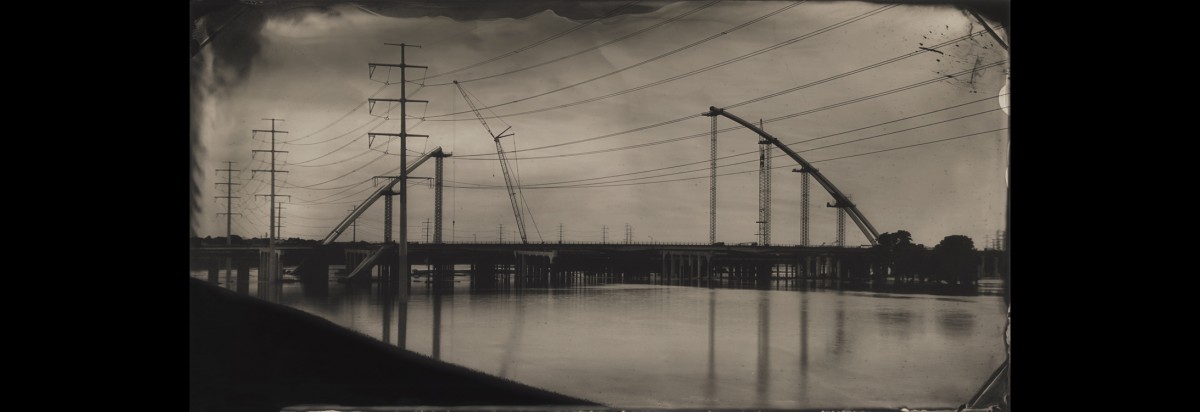

We’re in the photo lab in the Greenhill School in Addison with photographer Frank Lopez. He’s made a name for himself with photography’s “ghost” technologies – ambrotypes, pinhole cameras, tintypes – using their black-and-white imagery to capture not Cartier-Bresson’s famous ‘decisive moment’ but moods, blurs of life and culture, fleeting slips of time.

Lopez picks up a relatively recent ghost artifact: a classic, top-of-the-line Polaroid camera. This one’s officially a Land camera, the kind with a bellows and a timer, named for Edwin Land, the inventor and company owner. Lopez presses a button. The camera whirs, gears click – “That’s an old sound you don’t hear very often,” Lopez chuckles. Not anymore anyway. Once, millions of people would recognize the sound and this entire moment, the reveal of an ‘instant’ photo as the camera ejects a slim packet containing a photo and its negative. Polaroid cameras were hugely popular in the ’50s and ’60s because they took pictures and developed them right then and there, right inside the camera. You didn’t have to send off your film to be printed.

Frank Lopez in the Greenhill School photo lab with one of his Polaroids. Photo; Jerome Weeks

But truly instant, digital snapshots – like the ones we take all day, everyday, with our iPhones – they bankrupted Polaroid. Twice.

Yet here’s Lopez working with half-a-dozen of the out-of-date clunkers – regular Polaroids, large-format ones, even one designed for dental shots. And he has boxes of film that Fuji made to fit the cameras. The Polaroids are only one of the many old-fangled photo technologies Lopez uses in his artworks – and teaches to his high school students.

But why teach them – when iPhones and Instagram and Photoshop dominate their lives?

“The physical negative, a physical print, a physical object that you can work with,” he says, “those are some of the things we’ve lost going digital.”

The 50-year-old Lopez grew up in the family business, Lopez Auto Service. So with him, it’s all about getting your hands into it, your hands on it, taking it apart to learn how it works. But with digital, the inner process is sealed off. It’s hard to tinker with. And tinkering with the ‘how’ of things is often what inspires artists.

“I think there’s magic in process,” says Corbin Doyle, who teaches filmmaking and digital art at Greenhill. “And I think Frank would totally agree. In arts, the process can mean something.”

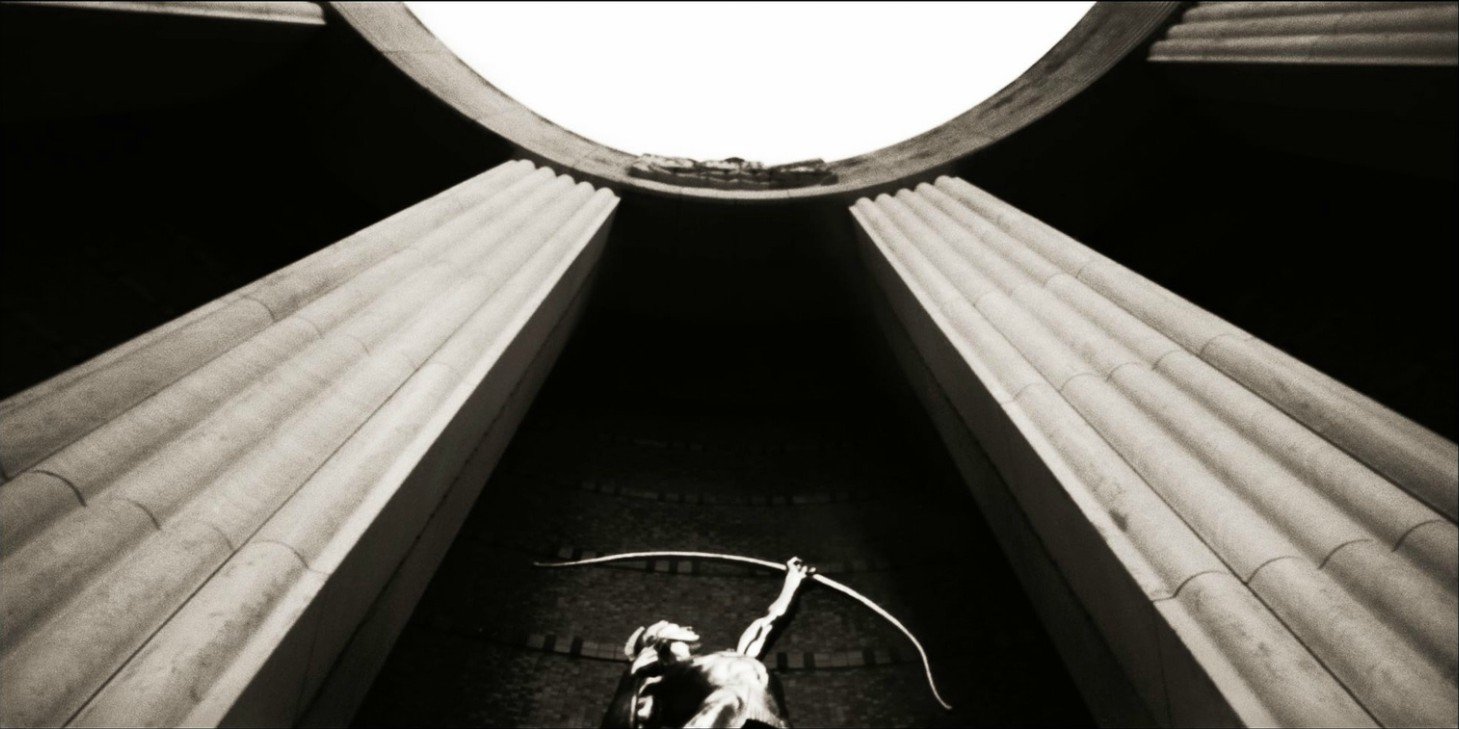

‘Tejas Warrior,’ the statue at Fair Park’s Hall of State photographed by Frank Lopez with a pinhole camera, 2015.

Ever since he got a degree from East Texas State, Lopez has been all about the process. He became known as a pioneer in North Texas, a pioneer of the Great Return of Analog: you know, vinyl records instead of the onslaught of music streaming, printed books experiencing growth in sales while e-books level off. A dozen years ago, Lopez lived and worked in an Exposition Park studio, mastering the old-time arts of the tintype, the pinhole camera and wet-plate photography. The kinds of things Matthew Brady used during the Civil War.

But then Lopez was hired by Greenhill. And he left Expo Park for Little Elm in 2015.

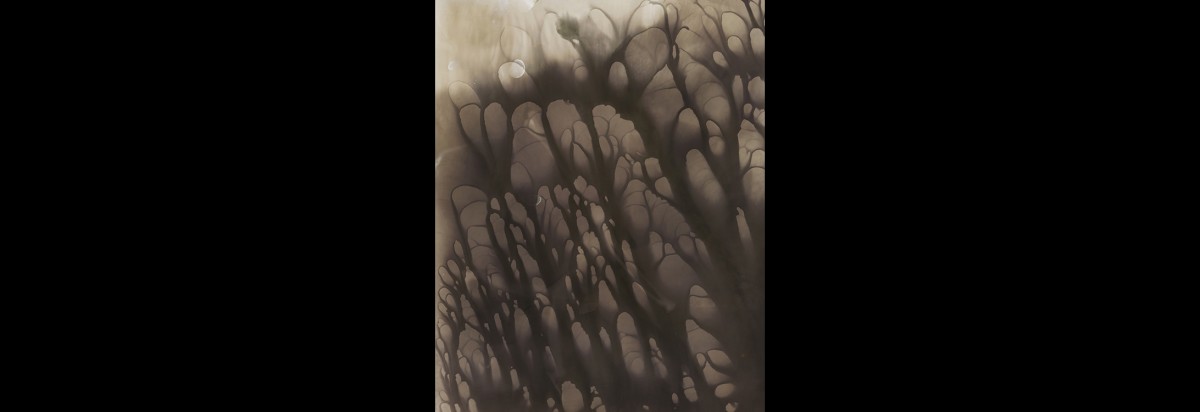

“Ten or twelve years ago,” Doyle says, “he came, talking about going back to all these materials. And there has been a massive transformation. He used to be image-driven. Now it looks like chemistry. And how cool is that?”

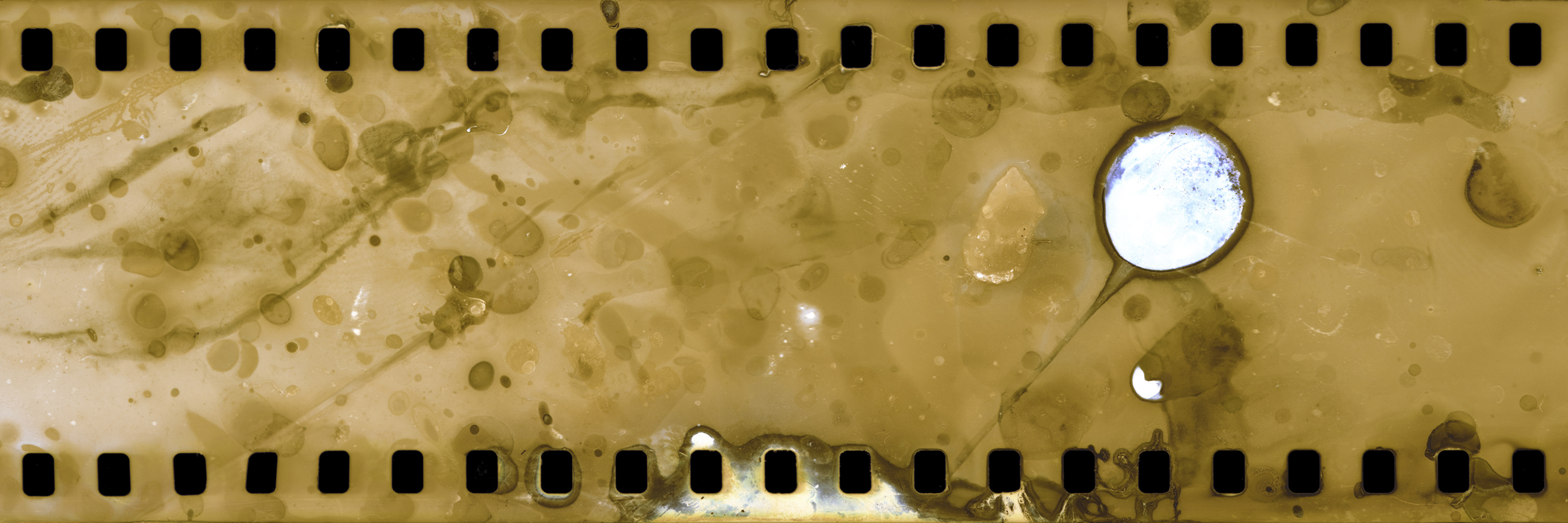

These days, Lopez uses iPhones and Photoshop. He turns digital photos into tintypes. He scars Polaroid negatives and makes them look like abstract paintings. He takes film strips and bleaches them into what look like flame-marked wrecks. And he digitizes all these images and sells them online.

Frank Lopez in Greenhill’s studio. Photo: Jerome Weeks

“That is a direct result of teaching,” Lopez says. “I have to teach digital. I have to teach a language that the students grew up with. But then I can also teach them how to shoot film and how to process film. I teach all aspects of photography to my students.”

Lopez calls his resulting artworks ‘antiquarian avant-garde.’

“Part of what’s so exciting,” says Doyle, “is that Frank talks about living in the 19th century, 20th century, the 21st century with every piece he makes. It’s in his blood, this idea of looking back and looking forward.”

Looking back, way back, Lopez can remember his very first photo. He was 8, his mother was driving in South Oak Cliff when farms and farm animals were still there. “And we saw a horse in a pasture,” he says, “and so she pulled out this beautiful old Polaroid camera. And she had me just point the camera at the horse and take the picture. I just remember that was magical, seeing things right there on the spot.”

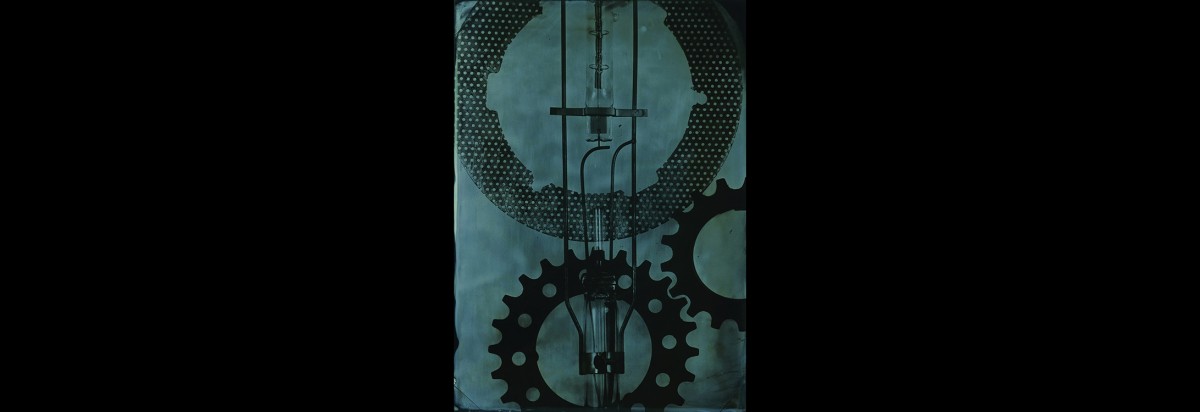

Looking forward, Lopez has been working on a brand-new series, images of discarded gears and utensils he’s picked up in Exposition Park. He touches these up digitally, making some look like industrial abstractions.

But the series looks back as well. The series will ultimately include images of his father’s tools. You know, the old ones, the ones Rayes Lopez has used to repair cars for 50 years.

When did you first consider yourself a photographer? Not, you know, I loved taking snaps as a kid, but when did you decide, This is it, this is my passion, my career?

That’s a good question. I kinda found myself falling into photography in high school. I had broken my collar bone and really had nothing else to do for the summer. And I picked up a camera and started playing with it. It was actually an old Pentax, so it was very manual, of course, we were years away from when digital was going to be created. So at the time I was going to become an auto mechanic. I was going to take over the family business, Lopez Auto Service, which is still in business after all these years since 1973, I believe. I did not find that to be my passion. I did enjoy taking things apart, putting things back together and learning how things work.

But after a full year of what basically became a gap year, I decided to pick up a camera again. And I was taking drawing classes at the time. A friend happened to say there’s a great school locally called East Texas State University in Commerce. I went to visit one day, and that’s when I decided to study photography as a major. It really wasn’t until much later that I realized I could make a living at it that I decided to call myself an artist and a photographer. A lot of my education was really hands-on.

‘Found: Filmstrip Yellow,’ chemigram, 2015

How did you make a living at it?

I became a society wedding photographer ini the mid-’90s — in-demand, worked coast-to-coast. I wasn’t doing all the typical set-ups, all the posed grinning. I shot with black and white film, on the go, breaking every rule you possibly could in Dallas society photography. It became much more about the interpretive moment. I had hand-made leather books made for the photos.

Why’d you quit?

I got burned out [laughs]. I was in-demand, working coast-to-coast, working at such an emotional level. And digital came on the scene and really changed the ballgame [by the mid-’90s]. A lot of photographers switched over, started just burning everything to disc and handing that over. And of course, there was a lot more money needed to produce your work in a hand-crafted way. Digital really kind of cheapened what it meant to be a photographer. We became devalued that way. And society photography was already a cut-throat business. So I was looking for a change.

Did you ever have to quit a day job to pursue photography? Or have you always combined photo work and teaching?

I actually went right back into education after I graduated. So I got a degree in photography, graduated in 1990. And I got a job, a full-time job at a local art school, running their equipment and becoming basically the lab manager. And I did that for a couple years, until they decided that I knew too much about photography to be working as a technical person, and that’s when I began teaching. So I did that for a couple years, transitioned into a professional printer, and so really, I’ve been involved with photography since Day One. And I’ve really not done anything else ever since.

What have you given up to pursue your art? Not necessarily, what did you lose? It could also be something you gave up happily.

There have been times I have teetered on the border of sanity – trying to find why am I doing this, what am I doing, what is going to be the end result here? So just finding frustration and running into frustration. However, the older I’ve gotten, all that stuff has gone away. It’s more about I’ve found a voice, I have something I’m very interested in. I wouldn’t say ‘passionate about.’ Passion is reserved for my family. Photography is a beautiful thing for me to work out certain internal emotions, things like that.

I’ve sacrificed a tremendous amount. I’ve lost relationships due to my frequent travels to China. It’s hard to go somewhere foreign and immerse yourself in that culture and then come back. You truly fall back into culture shock, where you don’t quite recognize around you what was once familiar.

‘Hawking’s Radiation,’ chemigram, 2017