new Aaron Aryanpur

ArtandSeek.net July 26, 2018 54Welcome to the Art&Seek Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the stories and artistic efforts being made by creatives in and around North Texas. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

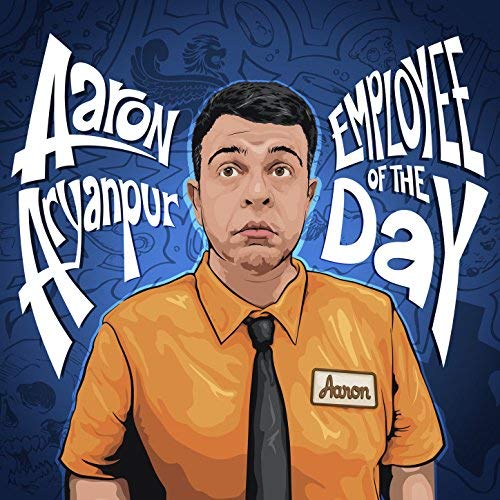

Stand-up Aaron Aryanpur has toured and been on TV. He’s become a mainstay in the Texas comedy scene. And he just recently released his second comedy album, ‘Employee of the Day‘ (which sports his own cartoonwork on the cover, below) and started a couple of favorite projects. So he’s having a big summer. For this Art & Seek Spotlight, we’re revisiting our profile of Aryanpur from last year.

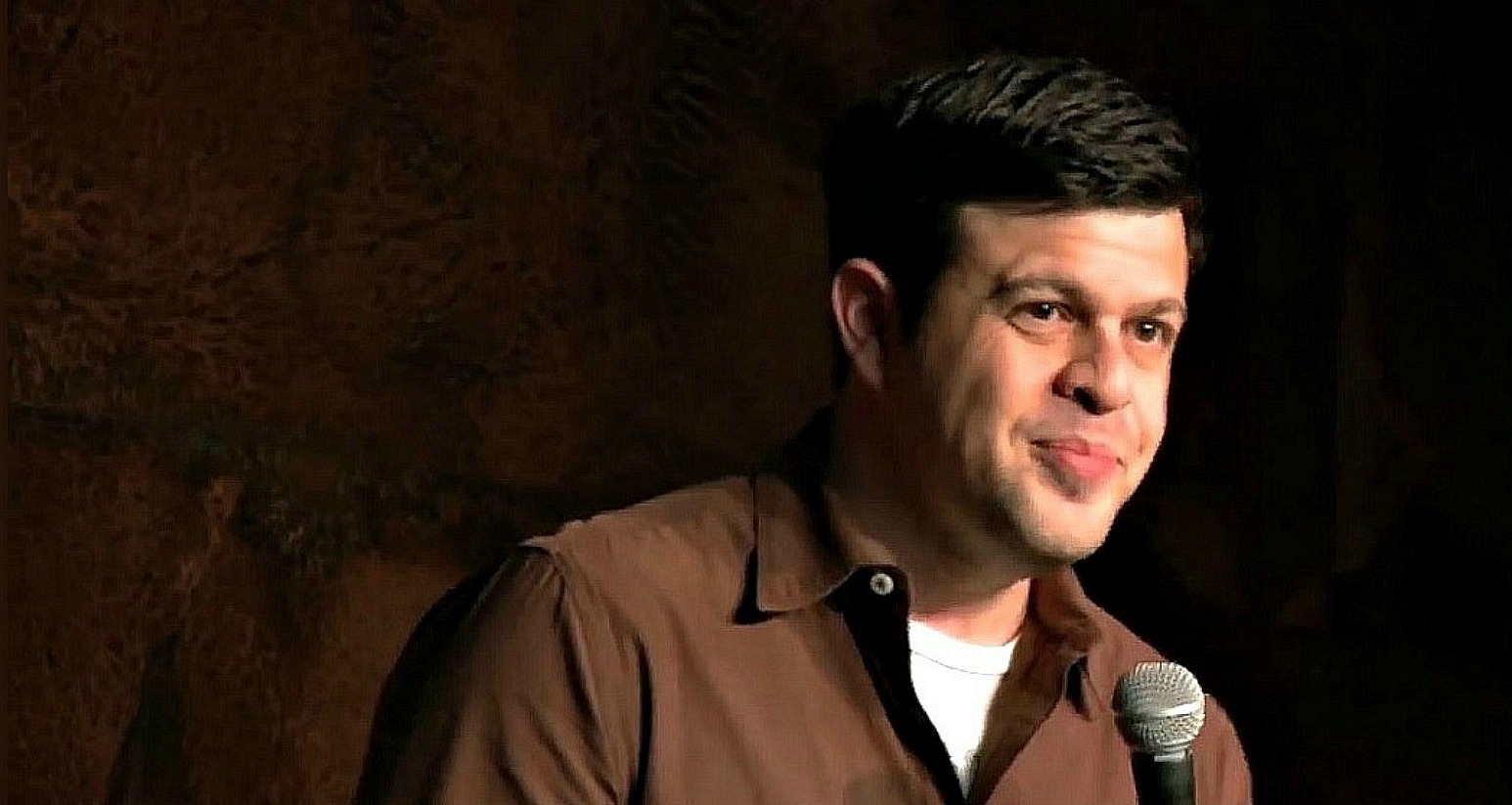

We’re at the Backdoor Comedy Club in Dallas, waiting for the headliner, the last comic of the evening.

“Ladies and gentleman,” the emcee crows, “please welcome, the incomparable Aaron Aryanpur!”

“Thank you. That’s great,” Aryanpur says to the applause as he gets to the mic. He actually seems grateful and happy to be here – he instantly sets an easy tone. “A lot of you are looking at me like you don’t know who the hell I am. That’s fine. If you’ve seen ‘America’s Got Talent,’ if you’ve seen ‘Last Comic Standing,’ if you’ve seen ‘The Tonight Show’ – I have seen all those programs as well, so we’re all on the same page.”

Aaron Aryanpur on ‘Laughs.‘

Actually, the North Texas comic has appeared on the Fox TV show, ‘Laughs.’ He’s toured with comic Maz Jobrani and shared a stage with Richard Lewis. This summer, he released his second album, ‘Employee of the Day‘ (which sports his own cartoonwork on the cover, below).

So Aryanpur’s being modest. And that suits his regular, family-guy persona. That stand-up persona is something he is and something he’s created. After all, he’s a guy who grew up in Denton, the son of an Iranian immigrant. Yet he deliberately kept Aryanpur as his stage name.

“Growing up here, I was always made to feel like I had to answer for my last name,” Aryanpur explains. “Not out of vindictiveness or anything like that. But that doesn’t mean that I didn’t grow up feeling like an outsider. I’ve had to live with this name, and I’ve had to explain it. I’m going to hold on to it, and I’m going to make you learn it.”

“The thing that’s weird about stand-up,” says Paul Varghese, “is that the audiences will eventually tell you how they perceive you.”

For more than 16 years, Varghese has shared stages and tours with Aryanpur. They came up together through the local scene. At different times, they’ve even been voted the funniest comic in Texas. But Varghese is an Indian-American with a dark complexion. Which is why, he says, he feels he has to address race in his comedy. Aryanpur has light skin; his ethnic background isn’t as apparent.

“He doesn’t fit their physical description of somebody from Iran,” says Varghese. “So the vibe they get is the guy that lives next door, you know. It’s very relatable.”

“I can pass – for whatever,” agrees Aryanpur. “I feel like I’m very nondescript. If I walk down the street, you’re not going to say, ‘There goes the Texan.’ ‘There goes the guy who’s Iranian, the Jewish guy.’ You’re not going to notice me at all.”

Ironically, he got his first real break because of his ethnic background. In 2002, after they’d barely started, Varghese and fellow Indian-American comic Raj Sharma created the Indians at the Improv tour. This was years before young Indian-American comics like Hasan Minaj, Mindy Kaling and Aziz Ansari became popular figures on American TV.

But as Aryanpur says of Sharma and Varghese’s plan, “they looked around for Indian comics and ran out after only two.” Varghese and Sharma needed a third for the gigs to work, and as Varghese remembers, “I said, ‘I know this Iranian guy, his name ends with -pur. Close enough.” To be perfectly accurate, it should have been the ‘Two Indians and One Iranian at the Improv.’

It didn’t matter. What the tour gave the three comics was access to gigs outside Texas, bookings that can take local stand-ups years to get. And the three played gigs that – to the surprise of club-owners – sold out because of the hunger of Indian immigrants and Indian-Americans and Iranians – basically, almost anyone from south Asia and the Arabic Middle East – to see and hear some of their own crack wise. That helped establish the three North Texas stand-ups with club-owners.

Aryanpur confesses that during the tour – and on subsequent dates with Maz Jobrani – to feeling ‘not Persian enough’ for the audiences. It’s not that Aryanpur avoids ethnic issues – as he says, they’re just not at the top of his mind. Not like the way he’s bugged by how his wife Nicole orders in restaurants. Or the way their two young sons have no idea about getting birthday gifts for mom.

“If you don’t buy gifts from the kids to their mom,” Aryanpur says from the stage, “there’s no initiative whatsoever. Pre-schooler’s broke. I don’t mind buying her the gifts, I’m just tired of coming up with the ideas. I’m out. ‘All right, boys, gather round, gather round. I need fresh ideas for mommy.

“Twelve-year-old, whatcha got? Nothing? Thanks.

“You. New guy. Any ideas?”

Paul Varghese performing on RIDE TV.

Varghese says, starting out, he and other Dallas comics felt Aryanpur was already the natural one onstage. But he was actually the youngest of the bunch.

“I think if anything that’s changed for Aaron over the years,” says Varghese, “it’s his material’s just better. Before, I think he was looking for observational stuff and now that’s not as important to him as talking about his family.”

Offstage, the 40-year-old Aryanpur is not the typical wisecracker eager to turn anyone talking to him into an audience. He’s extremely knowledgeable about stand-up and has thought deeply about it – about things like using his family life for material.

“They didn’t sign on for this,” he say of his wife and kids. “My wife had married me six months before I even thought about doing stand-up. So I try to keep that in mind and, you know, honor that as much as I can.” As grumpy as his routines get, he points out, he’s frequently the butt of the jokes.

When he started, Aryanpur says, he wanted to see if he could stand where Garry Shandling and Chris Rock stood. Nowadways, he says, it’s different. The comedy stage is the place where he gets to play. It’s where he doesn’t feel self-conscious anymore. It’s the one place, he says, he doesn’t even suck in his gut.

“It takes a while to stop being a caricature of a comedian and start being yourself,” he says. “And the moment you’re yourself, things really start to open up for you.”

Five years ago, Aryanpur turned down a major job offer as an art director to focus on his comedy. He still works part-time in design, but he has steady comedy gigs, corporate events, voiceover work . . .

“I got to work my first cruise this last fall,” he tells the audience. “I guess, technically, that makes me a cruise-ship comedian – which is, um, not the goal.”

So what is the goal? Well, stardom, of course. But Aryanpur says what he’d really like to do is an illustrated children’s book or an animated series, something that combines it all, his cartooning abilities – as seen in his ongoing web comic, ‘Next Window Please’ – plus his experiences with his sons, his writing and his comedy. Turns out, he’s got projects underway with both of those ideas, illustrated book and animation.

Comedy transforms things. It may sound trite, Aryanpur says, but it’s a little like the blues that way.

“You take all these things in your life where you felt mistreated or all the ways that you fall short,” he says, “and then you turn them into something joyous.”

There is, he says, nothing better.

How has growing up Iranian-American in North Texas affected your stand-up – especially with your name?

One of the reasons I wanted to do stand-up at the beginning was to give voice to that [Iranian-American] part of myself. Where it’s like, ‘I feel nervous about this.’ I don’t want to say ‘ashamed,’ but growing up here, in public school and whatever, I always was made to feel I had to answer for my last name. I always had to explain my dad and his complexion, explain where he was from. Not out of any vindictiveness or anything, nobody was being nasty about it.

But it’s one of the reasons I kept my name instead of a stage name. I’ve had to live with this name. I’ve had to explain it. I’m going to hold on to it, and I’m going to make you learn it. I’m going to make sure you know how to spell it and pronounce it. I’ve spelled it out phonetically backstage for emcees to read. I’ve seen hosts panic as they’re about to say my name, and I’m like, ‘Just say Aaron, I don’t care.’

So there’s a defensiveness there. You have to be ready with an answer. And that totally informed what I did onstage.

Of course, sometimes, I don’t feel Texas enough. When I’ve been on the bill, I’m playing Boston, and it’s like, ‘Hey, we’ve got this guy from Texas!’ And then I show up, and they say, ‘This is not the guy from Texas, the dude with the hat.’ Whatever. Everybody makes assumptions about Texas – we all know that.

Have you lost gigs because of your name? Been heckled for your background?

Have you lost gigs because of your name? Been heckled for your background?

No one’s spewed hate, nothing like that. And I should say one of the great things about comedy here in town, there are so many different comedians with so many different backgrounds, you couldn’t say what ‘Dallas comedy’ means, what ‘Fort Worth comedy’ means. For awhile Bill Hicks was like the voice of Houston comedy, even though he wasn’t living in Houston anymore. And so you had a scene that felt like, ‘That’s what a comedian is, that’s what I need to be.’

My friend Paul [Varghese] has mentioned this, too. There have been a lot of comedians who’ve done very well, both staying here and moving away, and they’re all very proud of where they come from. Bigger names – like Cristela Alonzo, she had her own TV series [‘Cristela’ on ABC], she’s going to be a car, the voice of a car in a new Pixar movie [‘Cars 3’] – or like Tone Bell.

Jamie Foxx?

Yeah, from Terrell. But the point is that all of them have different backgrounds. And it humanizes everybody. I love that there are both men and women from these backgrounds. For an audience who may have never seen an African-American speak to their lives, here they are. The comedy scene itself is very welcoming.

So I’ve never really got anything nasty while onstage – on that score. That being said, I’ve encountered the most polite of racism – offstage. When people have questions and they don’t realize they’re stepping over the line. Every so often, you run into someone who may be paying you a quote-unquote compliment not realizing how insensitive they’re being.

Paul Varghese says when you two were starting out, he and the other comics saw you as the one who was more comfortable on stage. Sure, you’d be nervous and go over and over your set list beforehand, but once you were out there, you seemed natural, more natural than they felt, certainly. Did that come – naturally? Were you ‘born for the stage’?

I think I was kind of comfortable onstage, but I was still nervous that someone might shout something out and throw me off. Or what happens if I forget a bit or what happens if I mess this up? What happens if this set goes terrible and they never have me back? There certainly were those thoughts. But doing it awhile, and going up on the same stages over and over, so you know what to expect, know what to do, and growing, knowing where you need to be growing, real confidence comes from all that.

Photo by Rosey Blair

A lot of comedians try to come off as just like the people in their audience – they dress down, they act casual. Make everyone comfy. It’s rare you get an aggressive comic like Anthony Jeselnick, who basically tells his audience. ‘I’m smarter than you, I dress sharper than you. You’re gonna have to keep up, little man.’ I’m not knocking that, he’s just such a strong contrast. And there are a number of comics who work in material like yours – the kind of ‘grumpy dad’ you get with Jim Gaffigan. So I’m curious about how much of the ‘average Joe’ persona you project onstage is cultivated, how much did you have to create? How much of it is just you being you?

One of the things I was told over and over again, and one of the things it took me awhile to learn, was that when you start out, you have all these affectations about what you think a stand-up comedian is. Even when you’re doing an open-mic in some basement bar, you talk a certain way, you have a certain cadence. What you’re doing is mimicking every stand-up you’ve seen, whether you realize it or not. If you have someone who’s really, really influential to you, somebody like a Chris Rock or a Richard Pryor or a George Carlin, you may go so far as to believe that’s who you need to be. Dress a certain way, speak a certain way, tackle certain topics. And slowly but surely, you have to chip away at all of that stuff to find out who you are. Because you can’t be Chris Rock, there already is a Chris Rock.

So you have to figure out what your voice is, you have to figure out what is important to you, what you find – not even funny. You’ re not looking for ‘funny.’ You’re looking for, ‘Where’s the truth in me? And then your job is to find how to properly communicate that truth to other people? And it takes a very long time to strip away all that – ‘You know what? I’m not going to be the hat comic. I’ll take that hat off.’ Or ‘I’m not going to be the polo shirt guy.’

You do try these different things to see what fits. And hopefully, what you’re left with at the end is just a slightly heightened version of who you really are. So unless you’re going to create a ‘character,’ unless you’re going out of your way to don a costume and change your voice, you’re only better served by being truthful, by being honest about who you are. If this is what you wear during your daily life, if this is what’s really important to you– the audience can tell.

Interview questions and answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.