Six Big Things You Can Learn About Dallas Racial History In “The Accommodation”

ArtandSeek.net September 13, 2021 97Jim Schutze’s The Accommodation has been called “the most dangerous book in Dallas” by D Magazine. That’s because, written in 1986, it viewed the city entirely through the history of race — from slavery to the “accommodation” of the title. That’s Schutze’s term for the under-the-table relationship that started in the ‘50s between the city’s white business establishment and some of Dallas’ more conservative Black leadership. This ‘one hand washes the other’ agreement, Schutze argues, was one, major factor that preserved white control of the city.

Jerry Hawkins, executive director of Dallas Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation, said, “This was one of the first books written up just about race in Dallas. Other major American cities have dozens, maybe hundreds of books like this, written about race. In Dallas, there are maybe 5 to 10 books like that, and that’s a shame, you know?”

Hawkins takes exception to some of Schutze’s argument: “It’s obviously just this one man’s take on this vicious racist story. But it is important. It’s important for sure.”

The Accommodation sold poorly on its release in 1987. But the eventual rarity of the first edition helped lend the book status as something forbidden or clandestine – and in demand. For years, it’s been available primarily through various sites as a downloadable file. Used copies online are regularly offered for $600.

In a rare development for a local history book that failed to sell, Deep Vellum is re-releasing The Accommodation Sept. 28 (pushed back from Sept 7). And Jim Schutze will sit down Tuesday with Dallas County commissioner John Wiley Price (who wrote a foreword to the new edition) for a public conversation about his landmark book. KERA will live-stream their talk.

Left, the first edition from Citadel Press (1987), the new edition from Deep Vellum (right).

Here are six facets of Dallas history you might not have known:

- White people began bombing homes owned by Black people in Dallas in the ‘40s, but the violence culminated in nearly a dozen dynamitings of Black residences in 1950-’51.

Severe housing shortages across America during and after World War II drove Black families and returning Black vets into all-white neighborhoods – in Chicago, Detroit, Harlem and Dallas. This triggered white violence and the spread of ‘white flight’ suburbia.

According to The Accommodation, what distinguished Dallas was the city’s response: The white establishment was unable to contain the racial angers of middle-class and blue-collar whites – while it also feared a possible backlash from Black people. Worse, the violence by whites endangered Dallas’ carefully mythologized, public image as a gleaming, business-minded city of opportunity, not another segregated Southern backwater.

So a “blue ribbon” grand jury was appointed to investigate the bombings. Its membership was a roster of Dallas’ white business elite but also included a Black attorney and two ministers.

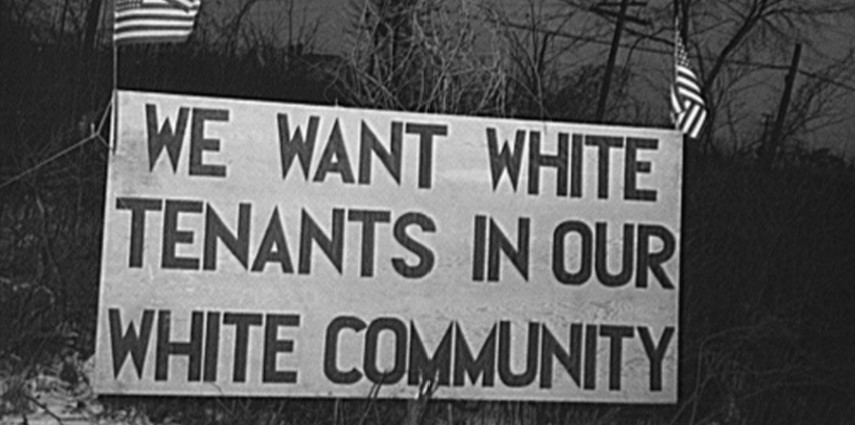

Detroit, 1942: White tenants tried to keep Blacks out of the Sojourner Truth Housing Project. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

- The bombings – and the reasons behind them – were swept under the rug.

The Dallas bombings terrorized the Black community — but no one died. So the “blue-ribbon” grand jury did not pursue homicide charges. It simply declared its work was done and asked to be disbanded — but only after the jurists also concluded “the plot reached into unbelievable places.”

What places? Nothing more was divulged. Or done. Case closed.

- Long-term, this kind of smoke-and-mirrors from Dallas’ business and civic officials often included a few compliant Black leaders to provide “consensus and cover.”

From the ‘60s and beyond, the white Dallas media and business community have proudly pointed to how the city quickly and collectively desegregated its lunch counters and buses.The Dallas Citizens Council, the committee of white businessmen who ran the city, wanted to dodge the glaring bad publicity and pressure that civil rights activists had brought to bear on other cities — especially after whites responded to them with violence. All of that was bad for business.

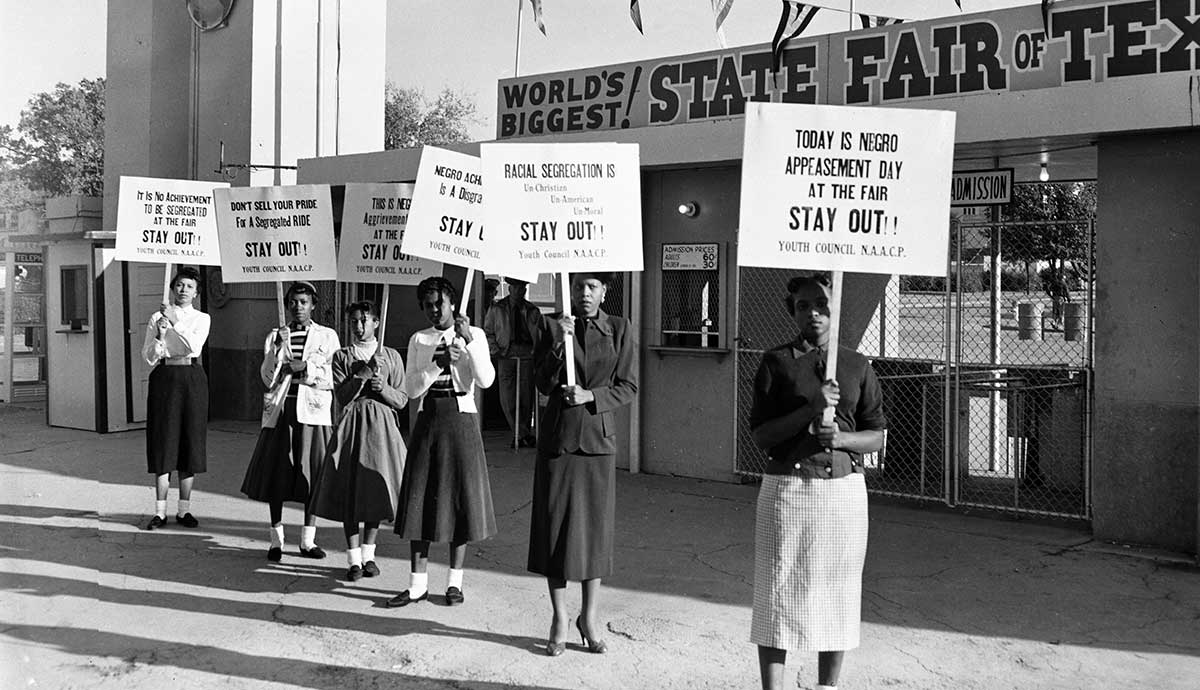

Even so, white Dallas still fought tooth and nail to preserve segregation — in courtrooms, classrooms, neighborhoods and the State Fair of Texas. And the city fought those battles for decades.Token gestures were made to secure “accommodation” from Black leadership, who became reliant on the white establishment’s approval and support to get even these gestures done. Schutze cites the creation of Hamilton Park (north of Forest Lane) as a neighborhood open to Black homeowners, devised to answer objections to the city’s segregation.

But it was just a showcase: Hamilton Park was itself a segregated area for only middle-class Blacks. For most Black people in Dallas, especially low-income and working-class ones, nothing really changed. Similarly, nothing really changed in the city’s segregated school system, despite highly praised efforts to include a handful of minority students.

NAACP Youth Council members picket State Fair of Texas in 1955. Photo: R. C. Hickman/Bullock Museum

- Dallas had other tools when it wanted to acquire Black-owned properties for private developers or civic projects.

The expansion of Love Field, the creation and expansion of Fair Park, the development of the Trinity River bottomland for a new industrial district along I-35: Much of modern-day Dallas may not have happened without the city’s willingness to use two things that its free-market faith normally abhorred, the use of federal money and eminent domain, the power of the city to take private property. And in these cases, to take Black-owned property at far below fair-market rates.

These efforts not only cleared land for commercial or civic development, they contained Black families in specific neighborhoods, permitted white gentrification and denied upward mobility to many Blacks. They could not use Americans’ chief method for acquiring and retaining family wealth: homeownership.

- Schutze contends that, as a result of all this, the civil rights movement that swept America from the ‘50s through the ‘70s was much less effective or forceful here.

This is possibly the most disputed argument in The Accommodation. To cite just one instance of early Black Dallas activism: In 1942, school teacher Thelma Paige Richardson sued the Dallas educational system — and won with her attorney, the future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall — to get equal pay for Black school teachers.

But among other things, Schutze cites such efforts as Jesse Jackson’s frustration over the failure of CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality) in Dallas and Dr. Martin Luther King’s visit to the city to help jump-start movement activism here. His speech was booed by some Black clergymen. It was King’s only visit to Dallas.

- Yet Schutze also argues, the single most significant blow to the white business establishment’s control of Dallas came with the Black-led lawsuits that finally secured the city council’s current set-up, with 14 councilmembers being elected by their districts and only the mayor running city-wide.

Previously, every city council candidate had to be elected city-wide (“at-large”). That way, no minority representative could gather enough money or enough votes to gain office. A successful candidate required the approval and support of the Dallas Citizens Council, the committee of white business leaders who made sure city government reflected their own goals.

Schutze contends that until 1990, when 14-1 permitted the city’s separate neighborhoods to elect their own council members — including Black and Latino candidates — Dallas never really functioned as a democracy. It operated more like a 15th-century Italian city-state run by a handful of wealthy families, with real power shared and traded amongst family members.

This was the long-term, suppressing effect of the accommodation: It prevented true representative politics from taking hold and operating in Dallas. As a matter of practice, citizens of all kinds didn’t have their elected officials get together and hash out their real needs, their preferred ways to live. The current administrative set-up is far from perfect, Schutze believes — the strong city manager system gives way too much power to the city staff and developers — but Dallas is no longer entirely stuck in some pre-civil rights time warp.

A final note: If you read Schutze’s book, you’ll find he quotes many people, some of them well-known (Stanley Marcus, District Attorney Henry Wade). But large portions of The Accommodation do not cite any sources, white or Black. Were people still afraid to talk on the record in 1986? How can we trust those sections?

Schutze said it was haste that caused the lack of footnotes or a list of sources. A major reason The Accommodation became such a seemingly ‘underground,’ contraband work was its bungled release. According to the author, Taylor Publishing was feeling pressure against releasing such an ‘anti-Dallas’ book and told him they needed to get it out quick — which is why it lacks sourcing. In the end, Taylor pulled the book entirely (it claimed pre-sale orders were low). Instead, the book was published by Citadel Press. Which quickly remaindered it after it sold poorly.

But as Schutze noted, since 1987, many of the arguments that he first advanced about Dallas’ racial politics have since been corroborated and expanded on by professional historians such as Michael Phillips in The White Metropolis (2006) and Henry Graff’s The Dallas Myth (2008).