The DMA Dodged A Major Headache By NOT Buying That Supposed Da Vinci

ArtandSeek.net April 17, 2019 18In “The Invention of the ‘Salvator Mundi,’ Or How to Turn a $1,000 Art-Auction Pickup Into a $450 Million Masterpiece,” Matthew Shaer in New York magazine tracks how the purported, now-famous da Vinci came out of nowhere to crash through the auction ceiling at Christie’s in 2017 for nearly half-a-billion dollars. At one point along the way, it had been seriously considered for purchase by the Dallas Museum of Art, courtesy of former director Maxwell Anderson, who got in fairly early in the rush to buy the work.

The Renaissance-era oil painting, Shaer writes, “has come to illustrate how the interests of dealers, museums, auction houses, and the global rich can conspire to build a masterpiece out of a painting of patchwork provenance and hotly debated authorship. Its rise is both an astonishing tale of restoration and historical sleuthing and — for those inclined to see the world less romantically — a parable of highbrow greed, P. T. Barnum–style salesmanship, and reputation laundering.”

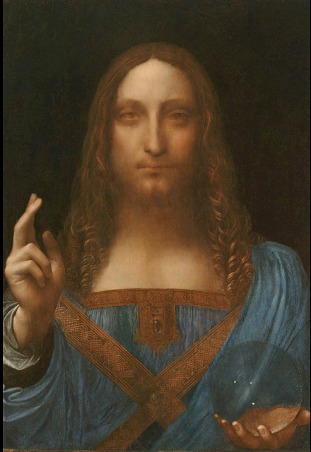

‘Christ Salvator Mundi,’ (Christ, Savior of the World), oil on wood panel, 26 inches by 18 and a half.

Basically, da Vinci’s original “Christ Salvator Mundi” (to give it its full title) was one of his most popular works in the 16th century, copied by dozens of painters, but the original was lost. So when an art speculator and a gallery owner spotted this one for sale on the website of a New Orleans auction gallery, they figured they’d found a possibly interesting copy. If they were able to connect it to a Leonardo-era painter, they might make a handsome profit on it, but only in the hundreds-of-thousands of dollars range. What they found was a badly damaged, badly restored panel painting with a single, re-painted thumb (different from other copies) that shot the work into a much, much higher league of historical argument, restoration and analysis.

Shaer quotes one ‘prominent art world source’ on how much restoration was required with ‘Salvator Mundi’: “You’ll get defenders of the painting who will say, ‘Look at a work like [Hans] Holbein’s The Ambassadors. That had loss too, and it was restored and repainted, and now it’s hanging in a museum!’ ” the source said. “Well, yes, but that loss was 5 to 10 percent of a very large painting. With all due respect to the immense talents of Dianne Modestini [who restored it], the Salvator Mundi was a much smaller picture, and the amount of required intervention was proportionally higher. And that should be a key area of debate: Where does conservation become invention?”

But after a number of renowned experts from Italy, New York and England did conclude it was an authentic da Vinci – and several disagreed, concluding that at most, da Vinci “was involved” – the painting was shown in a major Leonardo exhibition at the National Gallery in London – as a real Leonardo, period. And that’s when things went crazy because, alongside other da Vinci works, ‘Salvator Mundi’ looked a little sad.

Few observers issued as forceful a critique as Carlo Pedretti, a longtime scholar of da Vinci and a former chair in Leonardo studies at UCLA. In an opinion piece for the Vatican’s newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, Pedretti pointed out that years earlier, another Salvator Mundi, “a better version,” in his estimation, had been floated as the original. Whether it was — the scholarly consensus today is that it wasn’t — the public, Pedretti went on, should be cautious of “the sophisticated marketing operation” surrounding Simon and Parish’s version. “There is … much in circulation in the art market,” he wrote, “and it would be wise not to chase chimeras like the case of the ‘rediscovered’ Salvator Mundi, which in the end explains itself. Just look at it.”

But things really went crazy because by including a privately-owned painting in that show, the National Gallery basically gave it a stamp of approval, helping promote the work’s public profile and its cash value – by a huge amount.

That’s when Maxwell Anderson and the DMA enter the picture – as well as a multi-billionaire Russian oligarch named Dmitry Rybolovlev. And we’re not even halfway through the saga of why the painting has since disappeared, having been purchased by Prince Badr of Saudi Arabia yet never put on display in its announced home, the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

Well worth a read.