The Unheralded Woman Behind San Antonio’s Witte Museum

ArtandSeek.net November 1, 2019 21

Ellen Schulz with her camera.

THE WITTE MUSEUM

This fall marks 93 years since the Witte Museum first opened. San Antonio’s sprawling natural history museum has seen several iterations and huge growth, but largely lost in its evolution is the woman whose sheer determination created it.

See more pictures of the Witte Museum by going to tpr.org.

Ellen Schulz Quillin taught science at Main High School, trying in 1925 to plant the seeds of curiosity in her young students. And Witte CEO Marise McDermott said the seeds she cast were bluebonnets.

“She organized her students and other people to sell bluebonnet seeds to buy the first collection, a natural history collection called The Attwater collection,” she said.

McDermott said the collection was made up of a wide variety of pecans, natural history items and animal specimens. The students raised $5,000 — that’s more than $74,000 in today’s money — to buy it.

“She loved getting young children excited about history and our natural history,” she said.

And so the Witte Museum began with that single collection, paid for by Quillin’s ingenuity and student fund-raising, and housed in a high school classroom. As to the origins of the Museum, as we know it, that goes back to Mayor John Tobin’s card-playing friend Alfred Witte, who died in 1925. In his will he left $65,000 to create a museum, which was then matched by the city.

The entrance of the Witte Museum today.

CREDIT JACK MORGAN

“So Mayor John Tobin got in his car drove up to where we are right now which is the bend of the river and the third entrance of Brackenridge Park, which he declared that was where the Witte Museum was going to go,” McDermott said.

Thus in 1926, the Witte Museum was born. Writer and Museum Consultant Sherry Kafka Wagner says Quillin gave the fledgling institution creativity and edge.

“She was way ahead of her time because she always understood the museum to be a living place and she always thought about what the people needed and she said we need some place to go on Sunday afternoons, other than just downtown to the movies,” Wagner said.

Ellen Shulz Quillin also geared the Witte toward what is now called “Lifelong Learning.”

Art classes were offered at the Witte Museum as part of what is now called “Lifelong Learning.” CREDIT WITTE MUSEUM

“So the museum not only had things for people to see but they had weaving classes, pottery classes, art classes, special classes for children, lectures, dances,” she said.

But just three years into the wonderful Witte Museum experiment, a national tragedy: The Depression. The depression killed many non-profits and keeping the Witte open required creativity to compel people with little money to keep coming back.

For this reason, Quillin created a reptile garden full of snakes, turtles, alligators and lizards, which was wildly popular. And despite the garden’s touristy nature, the rattlesnakes there were used scientifically, to study snake venom. Wagner took her daughter there in its heyday.

“My oldest daughter when she was little we saw the Reptile Garden right before it ended. And she’s never forgotten it. She loved the reptile garden!” she said.

Quillin’s marketing creativity powered the Witte through the Depression, but McDermott says the institution’s use of scientific method elevated its reputation. She organized and funded scientific expeditions to the Lower Pecos River in West Texas to reveal more about those who lived there thousands of years ago.

“Many universities including the Smithsonian who came after that, did massive expeditions throughout West Texas. But Mrs. Quillin and her team were the first to record these shelter sites,” she said.

Throughout the life of the Witte, these expeditions continued, as did efforts to preserve and protect rock art sites.

“And these rock art narratives today are considered globally important,” McDermott said.

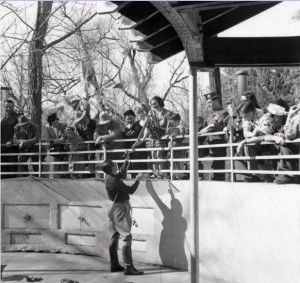

Inside the Reptile Garden at the Witte Museum. It was created during the Great Depression to keep guests coming.

CREDIT WITTE MUSEUM

Just in the past two years, the Witte has taken ownership and the duty to protect the entire White Shaman Preserve where prehistoric artworks adorn the cliffsides and canyons.

“She said there’s so much to learn about these people and that we really have to we have to spend more time doing that,” McDermott said.

Sherry Wagner added that unknown to most about Quillin’s 34 years running the Witte is that she gave floor space and encouragement to those who would go on to create the San Antonio Museum of Art, the Botanical Gardens and other local cultural mainstays. And that without that encouragement, the city would be a lesser place.

“San Antonio would definitely be the poorer place. I mean can you imagine? We would miss the Witte so much and the art museum and the Botanical Gardens,” Wagner said. “We’d miss all that a great deal.”

McDermott said she believes Quillin’s effects on the city, and on science in Texas are hard to measure.

“I can’t imagine San Antonio without the Witte Museum which, again, is here because Ms. Quillin,” McDermott said.

Two years ago the Witte completed its 65,000 square foot, $100 million expansion. As you walk into the Witte Museum under the Cessna-sized birdlike Quetzalcoatlus, a recreated dinosaur that used to fly here, you also walk under a great limestone arch. A small engraving on it recognizes the woman whose singular vision and tenacity created one of the state’s largest and most popular cultural institutions. A woman driven by the belief that science could explain the world if we just gave it a chance to.

Jack Morgan can be reached at Jack@TPR.org and on Twitter at @JackMorganii.