David Bowie Changed, Even Defined, The Music Video – As Video

ArtandSeek.net January 13, 2016 17

David Bowie in the original ‘Space Oddity’ video in 1969. Image above: from ‘Heroes.’

Much has been written about David Bowie, his importance to music, to culture, and so much more. But after his passing I want to talk about how this man — whom I never met or spoke with — had a profound influence on my life. If you know anything about me, you probably have guessed that what I want to talk about are his videos, his groundbreaking, trendsetting music videos.

Back in the very early ’80s, I was a film-film-film guy who had not much use for video. I was into the craft and teaching of CINEMA. Then one night I was at the Ritz Club in New York City watching a band (I think it was the Bush Tetras), and between sets there was this mastic screen showing all kinds of crazy video. It was like a ’60s light show without the psychedelia. At one point, I saw a snippet from an obscure German experimental film mixed with cartoons and other fascinating material.

David Bowie in ‘Ashes to Ashes,’ directed by David Mallet in 1980.

But then that stuff faded out and I saw ‘Ashes to Ashes’, the David Bowie video (directed by David Mallet). I was amazed. Bowie was a great performer (he was a mime), and you can see the intelligence of storytelling though this video. It had elements of cinematic storytelling but it was also clearly something else. It had this video effects edge. I knew there was something to this music video thing, and it changed my whole aesthetic approach to looking at moving imagery. It was a conversion experience. I brought On The Air and Video Bar to Dallas — expressly for people to experience music videos.

While many other people can claim to have invented music video, this video — for me — really solidified what the music video could be. It established what performance and imagery could be. It draws attention to its video nature — with video images inside video images. As such, Bowie is the D. W. Griffith of Music Video (silent director Griffith — creator of ‘Birth of A Nation,’ among other breakthroughs — is said to be responsible for creating modern cinematic language, including the use of camera placement and close-ups to heighten tension and even advance a story). Because of his stage training, his interest in costumes and fashion and visual art, his exploration of performance personas, his drive to wed his music with unconventional imagery that wasn’t a literal representation of either his concerts or his lyrics, Bowie took to video as a perfect extension/expression. His first ‘music video,’ after all, was ‘Space Oddity’ — made in 1969.

David Bowie in ‘Fashion,’ directed by David Mallet.

In ‘Fashion,’ Bowie’s next video (again directed by Mallet), he did something else that was important for the history and aesthetic of the music video form. In the video, he sings into something that looks like a mic stand but is actually a “C stand” (it’s used in lighting). The point is there’s no microphone. He’s not singing into anything that would record or amplify his voice. It’s clear at other times in the video that dancers, old ladies and other performers are lip syncing the song.

Visually, Bowie is saying, at this moment, you are not hearing the voice I am singing with — meaning, this is a different kind of performance of the song. It is something else, something self-consciously aware that a video performance is not the same thing as a live concert performance. It is “not the song.” This idea of the non-performance performance video is underscored with a particular, almost throwaway shot: When we see the drummer hit the bass drum pedal, there is no bass drum. All we see is the foot pedal moving, hitting air. The drummer is simulating a ‘performance’ of the performance of the song but in a way that explicitly indicates this isn’t even a ‘re-enactment’ of a live concert.

I know that last paragraph sounds like a big ‘So what?’ But the video and the techniques Bowie used helped to develop what, at that point, was a growing language of what music videos could be. It calls attention to itself as video.

Another way he influenced music videos was his interview on MTV in 1983 — which you may have seen. In the days since Bowie’s death, it’s been widely posted and viewed. That’s because, while being interviewed by MTV host Mark Goodman — in the days when MTV was the big, new force in popular culture — Bowie holds the music video channel’s feet to the fire over Time Warner’s conscious neglect of black music videos. Goodman’s lame defense is that MTV needed to attract viewers outside LA or New York — mid-Americans who might not watch videos with black performers.

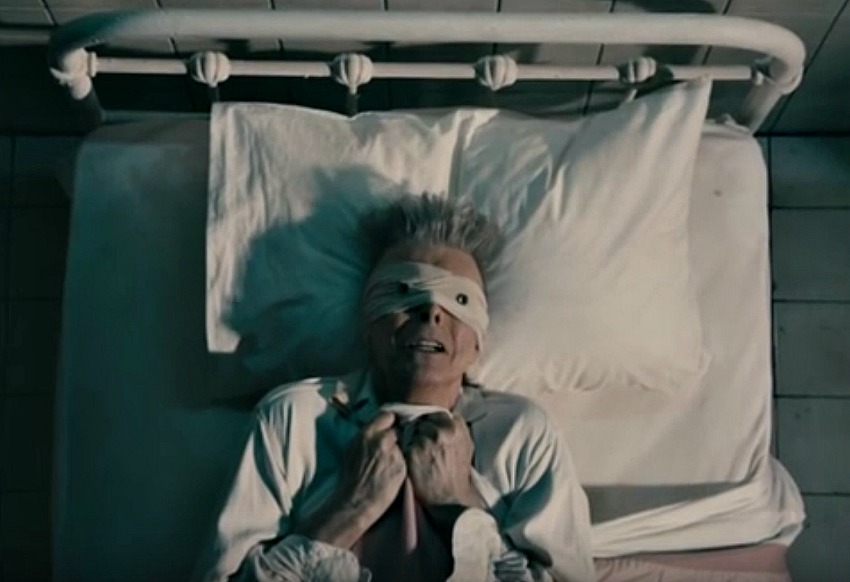

David Bowie in ‘Lazarus.’

What’s not stated in the interview is that, in particular, MTV wasn’t showing any videos by Michael Jackson. He was already one of the most popular entertainers on the planet — even in middle America — and in his dance performances, Jackson was a major influence on the music video. But even such a landmark video as ‘Beat It’ (made in 1983) wasn’t being broadcast on MTV. I hope this interview helped them see the light: Jackson’s videos soon broke the ‘color barrier’ on MTV, but it wasn’t until much later that the channel started the ‘Yo MTV Raps’ show, which brought hip hop to a nationwide audience.

Of course, any discussion about Bowie’s videos has to end with the end. The ‘Lazarus’ music video (directed by Johan Renck) is the best exit we have even seen from any artist (“Look up here, I’m in heaven … Look up here, I’m in danger. I’ve got nothing left to lose”). It’s better then the end of any series, movie, book — anything. The video was released two days after Bowie’s death and it was the best gift he could have given his fans. But more than that, he got to shape people’s last impression of him as a man, as a singer, a performer, an artist, a man who changed the way we think of music and music video. A man who had so much influence on us, and on me.