Do Not Try This At Home: Marshall Harris, From NFL to Art

ArtandSeek.net July 6, 2016 25When I enter the sunlit showroom of Fort Works Art gallery in Fort Worth’s Cultural District, I’m not too sure what I’m going to see. I had only recently learned about the gallery via Instagram.

As I walk through the door I see what looks like a photo of a nude man, bald with a mustache. He resembles the British actor Tom Hardy in the movie “Bronson.” “Do Not Try This At Home,” warns a sign. Suffice to say, I am intrigued.

The entrance to Fort Works Art.

Photo: Fort Works Art

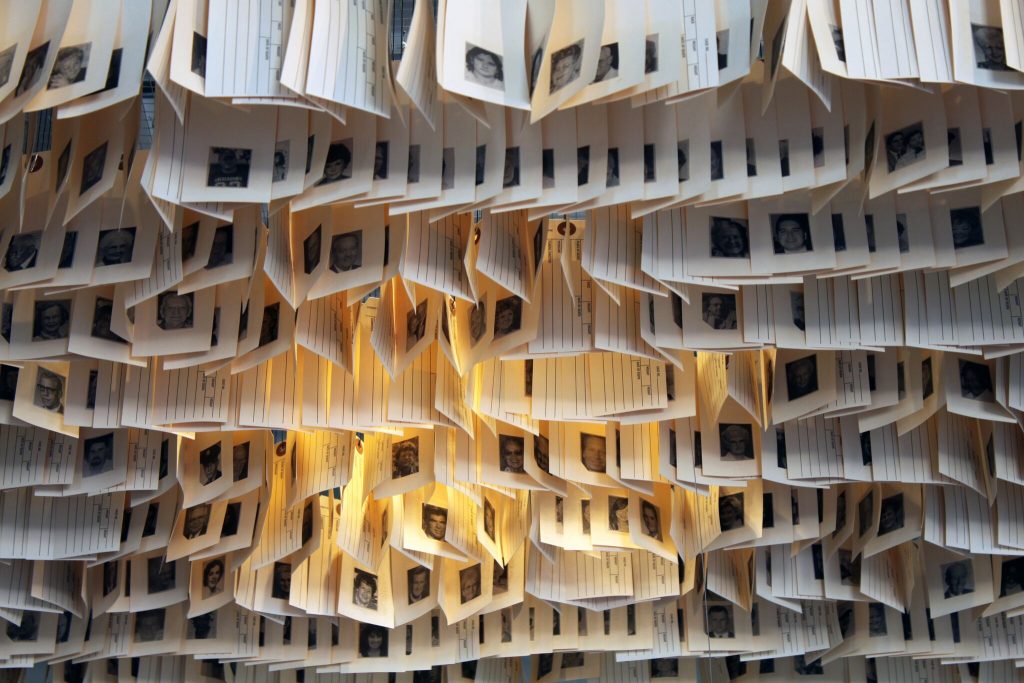

In the space, there are nudes, like “Onslaught” or “Magdalene.” There are some still life drawings. But what really grabs me is a large installation in the middle of the gallery, a 20-foot long drawing of the sky, with a couple thousand tags hanging above it.

I make a bee-line toward it to find out what the tags are.

“Those are toe tags,” says Caroline Dorris, a small and sharply dressed woman walking toward me. “The photos are from individuals’ obituary pages and the sky is a graphite drawing on Mylar. All of the pieces are. Except for one print.”

Marshall Harris’ “Slipping the flesh and bone of this moral coil”.

Photo: Fort Works Art

Dorris tells me about the artist. “He’s a large man,” she says, “probably like 6’8”. He’s from Fort Worth. He played football at Texas Christian University back in the 70s. He even played in the NFL.”

I thought to myself, “I need to speak to this guy.” So, I did. . .

Always An Artist, Hardly A Jock

Marshall Harris was a 6-foot-6 senior at Southwest High School in Fort Worth in 1974. He was an all-district defensive lineman and he had the opportunity to play at some of the premier football programs in the nation (Texas A&M, Oklahoma State) but he chose to stay at home and play at TCU.

The 1970s weren’t great for the Horned Frogs football program. During the decade, the team had one winning season and three with 10 or more losses. But, football wasn’t Harris’ number one priority. “When I was choosing a college, I wasn’t choosing a football team,” Harris told D Magazine in 1977. He was looking for a good commercial art or architecture school and TCU had a great commercial art program.

Harris says he was always interested in art. A nun at his elementary pointed out his skill to his mother. “She asked my mom what sorts of extra activities I was involved in, and my mom told her that I took piano lessons. She asked if I was any good and my mom said ‘no.’ Soon after I started taking private art lessons,” says Harris.

Portrait of Marshall Harris

Photo: Kevin Marple

Harris’ interest in art continued, but he says that if you’re a big kid that can run good and tackle folks in Texas, everything else takes a back seat. So, he played ball until 1985, when he officially retired from the National Football League.

Along the way, Harris was catalyzed by his love for art and by instructors like his high school art teacher Betty Smith. “Betty let me do my thing,” say Harris, “Betty never put any reigns on what I could do. If I wanted to make my drawing three-dimensional she let me. If I wanted to build some weird contraption with ball bearings or whatever, she never told me that’s NOT the way to do it.”

Harris says it was at that point that he became interested in all forms of art. Not just drawing or sculpting, but everything. This freedom made him want to study art in college and it helped him ensure that he never became pigeon holed in one form of art.

Life After Football & America’s Tragedy

After the NFL, Harris began to put his commercial art degree to use. He worked in advertising, marketing and even executing concepts for exhibit curators. The work was interesting, but Harris wanted to work on projects that were closer to his heart.

On September 11, 2001, Harris was in New York City for a trade show when two planes crashed into the World Trade Center towers. “Events like [9/11] shake [expletive] out of your head. They open your eyes. That day, I decided I couldn’t create stuff for other people anymore,” says Harris.

Harris’ commercial graphic design period was fun but it was over. He would no longer contribute to what he calls the “aesthetic landfill.”

An example of Marshall Harris’ commercial graphic design work.

Photo: Marshall Harris

In 2008, Harris began working toward a master’s in Fine Arts from University of the Arts in Philadelphia. He wanted the degree in case he wanted to teach, but his time in school led him toward sculpture and eventually, back to drawing.

Harris graduated with his masters in 2010 and in 2013 he won the prestigious Hunting Art Prize.

“Round-Up,” a drawing by Marshall Harris

It Looks Like Heaven

Harris moved back to live with his parents in Fort Worth after getting his MFA. They had a morning ritual, reading the obituaries in the “Fort Worth Star-Telegram” in order to “keep up with their friends.” “They claim that reading the obits is like an old person’s Facebook,” says Harris, “If they didn’t spot their friends in the obits, then they’d know their friends were still around.”

Photos attached to toe tags, a detail from “Slipping the flesh and bone of this moral coil” by Marshall Harris.

Photo: Marshall Harris

This morbid practice set something off in Harris’ mind, so he asked his parents to save the obituaries every day for a year. He wasn’t sure what he was going to do with them quite yet, but he knew he wanted them. After a year, he decided that he wasn’t interested in the text. Instead, he cut out the picture of every individual.

“I thought about reading every one of the obituaries, but that would just take too long,” says Harris. “Having a photo of each individual seemed sort of more authentic to me because we all live lives, but at the end of the day the only thing people will have of us will be our photos.”

That’s why there is no information on the toe tag each photo is attached to, Harris says. All he wanted to present was the person. Their face. The face is familiar, we feel like we recognize it; the story isn’t that important to someone who doesn’t know the deceased, he says.

Those faces dangling above the graphite sky look like they’ve moved past this world, possibly to the next. Harris says that he wasn’t trying to create heaven with “Slipping the flesh and bone of this moral coil,” but if that’s what you see when you look at it, it’s okay with him.