Review/Interview: The ‘Disagreeable’ Pleasures Of Jean Arp

ArtandSeek.net September 26, 2018 21Achieving the beautiful was not a chief priority of Dada – to put it mildly.

And mildness wasn’t high on their list, either. Dada – the “anti-art” murderers’ row that popped out of Zurich, then Paris, Berlin and New York even before World War I had ended – was marked mostly by a cackling absurdism and spiky intelligence. It aimed to shoot the wounded and finish off what the Western Front had already started when it came to all the dishonored wraiths that still staggered around the trenches – classic conventions like rationality, beauty, patriotism, glory.

Among these anarchists, Jean Arp stands out as the only Dadaist to create truly graceful artworks. OK, you’re right, we’ll grant Man Ray his silky experiments with photography. Otherwise, the major Dadaists – Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia – were a wrecking crew, more concerned with the irrational, the discarded, the paradoxical, the piercingly analytical. They worked to destabilize the traditional object, the painted space, the very idea of artistic illusion.

‘Human Concretion,’ marble, 1934. All photos: Courtesy of the Nasher Sculpture Center.

Arp thought deeply about those things, too, actually, but in contrast, he brought a lovely touch to the whole excavation, a touch instantly recognizable in any medium he employed, wood or plaster, bronze or paper. His style is intuitive, sensuous and charming. It’s probably one reason he was underrated for so long: Charm is easily dismissed. His work doesn’t seem entirely serious. They’re not a wild sarcastic take-downs like the other Dadaists hurled – they’re more bemused. His rubbery-looking things are more like Fisher-Price toys. You half-expect them to squeak if you squeeze them.

Yet they meld the impeccably precise with soft curves and the seemingly casual. And they remain astonishingly fresh. The works haven’t dulled the way so many of the more aggressive, more ambitious avant-garde provocations have. Walk into a room full of Arps today – we have that luxury, courtesy of the Nasher Sculpture Center’s wonderful new retrospective, ‘The Nature of Arp’ – and one is astonished these works weren’t made last week.

And one is struck by delight. With Arp, the heart floats.

Arp took Cubism’s chunky abstractions and made them into sloping torsos. Their langorous protrusions somehow slide past lumpishness and achieve the caressable. His biomorphic curls and holes influenced Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. His whimsy anticipates Alexander Calder. Paint his sculptures crazy colors, and they’re Ken Price’s sea worms or Tony Cragg’s swirls.

In Zurich during the Great War, Dada was a little buzz saw of cabaret performances, chanted nonsense poems and newsprint collages that look like a hurled typesetter’s drawer. It’s almost freakish how Arp was an active member of it, yet seems so distinct. He certainly shared Dada’s interest in the random, the radically unconventional. Yet he came out of that period with a personal aesthetic of fluid forms so appealing and so consistent one can only imagine George Grosz snarling and poking them with a stick.

This impression of Arp’s instant maturity as an artist is helped by his destruction of any early efforts; we can’t trace his trials-and-errors. So he appears, fully born, fully Arp – much like many of his works, which seem wholly singular, wholly themselves (although much credit must be given his wife, Sophie Tauber-Arp – which Arp often did. And conveniently enough, the University of Chicago Press has just released a new biography, ‘Sophie Tauber-Arp and the Avant-Garde‘).

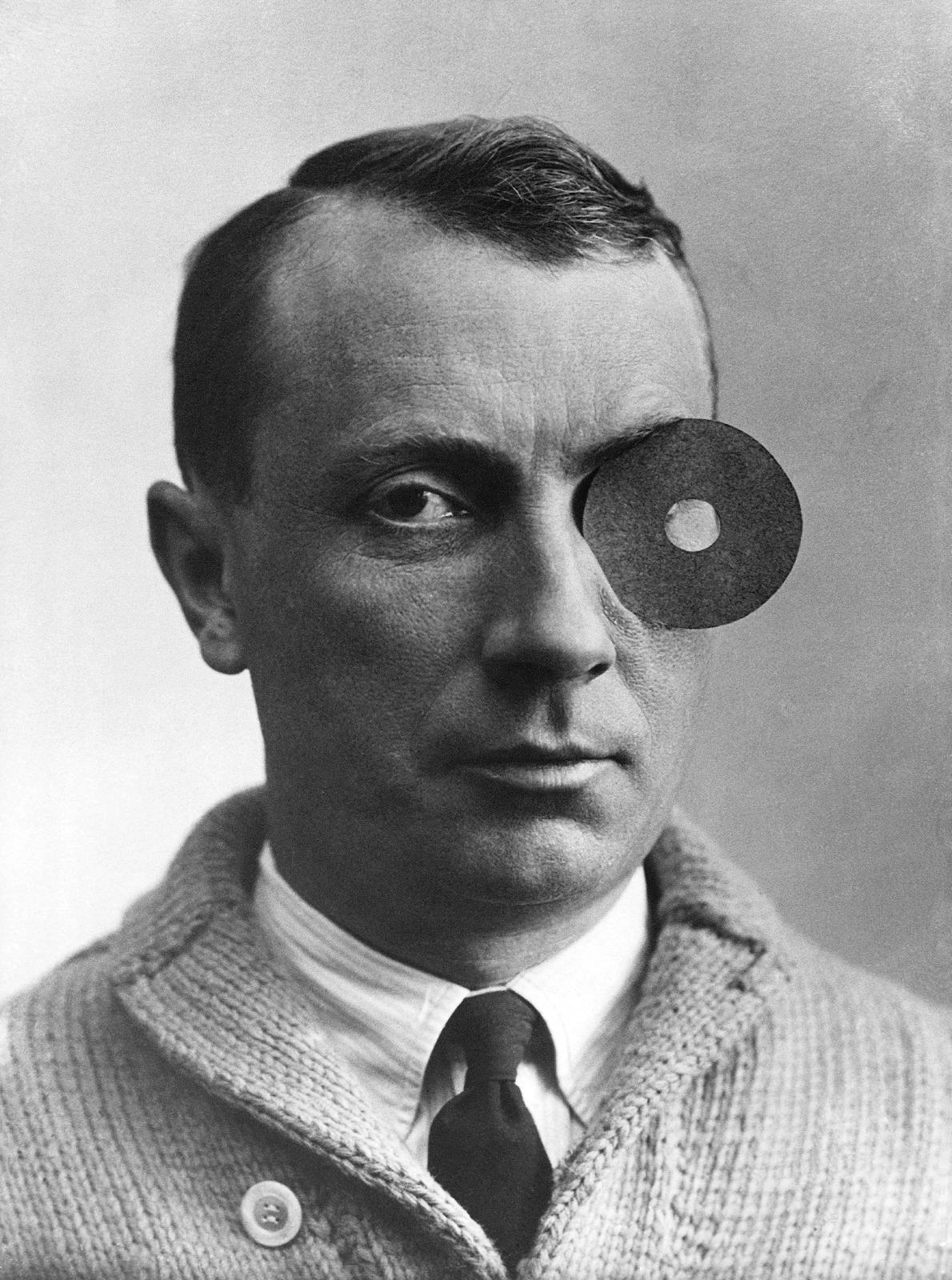

Jean Arp, self-portrait, photograph, ca. 1922.

Which brings us to curator Cathy Craft and ‘Three Disagreeable Objects on a Face.’ Craft chose ‘Disagreeable’ for the cover of her exceptional catalog and the show’s iconic image. Arp’s ‘Disagreeable’ was created in 1930 and first shown in 1933. It was the first of his sculptures in the round to be exhibited (as opposed to his layered, wood collages that hang on a wall). It was the plaster precursor of all the free-standing figures that followed: his bulbous limbs, heads, torsos, plants and lobster-like thingies.

The following excerpts from my conversation with Craft have been edited to make me sound wiser and more amusing:

Describe ‘Three Disagreeable Objects on a Face.’ It’s about as big as a medium-sized watermelon, wouldn’t you say?

You could say it’s about the size of a medium-sized watermelon. Or I’d say a raccoon. I’m laughing because those are comparisons Arp would like as he thought of his work very much in terms of connections to the natural world.

Which is the argument you make in the book. That Arp rejected the realistic ‘illusion’ of art, the attempt to simulate appearances. He wanted forms that were ‘life-like’ in that they could be their own species – almost like embryos.

Arp liked forms that appeared to be both abstract yet had references to natural things around us. He was very skeptical of classical, representational art. He wanted to give his works more freedom for interpretations, to let in other emotions like humor and not control the viewer’s response.

With ‘Three Disagreeable Objects,” he wrote a poem about it. He was a well-respected, playful and creative poet in both French and German. But we don’t know whether the poem inspired the work or came after.

In the poem, Arp describes awaking from a deep and dreamless sleep with disagreeable objects on his face: They were a large fly, a mustache and a little mandolin.That’s actually the work’s sub-title. ‘Three Disagreeable Objects on a Face: A Fly, A Mustache and a Little Mandolin.’

It’s nice he’s so precise. Like a scientist classifying specimens he’s come across.

Some of these things are certainly possible. You could wake up with a fly on your face and it would be disagreeable. You could wake up with a mustache. It’s unlikely, but if you’d been asleep for a very long time or if someone was playing a joke on you, perhaps. A little mandolin, on the other hand, is quite unlikely. And all three at once? It’s almost impossible to imagine.

Arp describes his response to the three objects by saying that after his wife told him what they were, he decided he’d just lie very still so as not to disturb them. And the poem says he goes on lying there. His wife takes a trip to Italy, the summer passes. Eventually, the objects kind of burn away on their own.

So it’s this dreamlike episode during a period when Arp was friends with and exhibiting with many artists and writers in the Surrealist movement, and the Surrealists prized dreams as unlocking the doors to our secret desires, as a way of opening possibilities beyond the conventions of the everyday world. And Arp seems, in a playful way, to be tapping into that interest in dreams.

‘Mountain Navel Anchors Table,’ gouache on board with cutouts, 1925

Yes, we can say that Arp is frequently pulling our leg. Or maybe it’s Surrealism’s leg. Not just with his whimsical titles but also his repeated interest in goofy shapes: navels, mustaches, buds. If it weren’t for the erotic quality of some of the torsos, his work would seem to be almost entirely bent on being clear-eyed yet child-like,

Humor was really important to Arp. Especially during and after World War I, humor was for him a great antidote to all the pomposity and pretension that came with military society and the nationalism that had led to this really disastrous war. Often, Arp’s writings have some kind of parody or satire of official language. Or they lampoon masculine posturing – like the mustache that often appears in his work. It isn’t a little, fine, Hollywood mustache. It’s usually this very robust thing that looks like a caterpillar with a life of its own, like something Kaiser Wilhelm would have had. Or any of Arp’s strict German schoolmasters when he was a boy.

We should probably state the three objects don’t really look that much like a fly, a mustache or a little mandolin. Perhaps the mustache does. But mostly they look like slugs. Or maybe baby seals.

Of course, one of the interesting things about this sculpture and often about Arp’s work as a whole is that the objects in the sculpture, none of them are realistic representations or even recognizable versions of any of these four things. They are open to interpretation. The forms are very similar to each other, but if you know the title, you can sort of make them out. But each of the elements has carefully modulated curves, they each sort of nestle and fit nicely into the face form.

But originally, the three objects could be relocated, you could switch them around. They weren’t fixed. As if to say, come play with these.

Just as he was ready to mock or subvert artistic conventions like representation, Arp was skeptical of other solemn aspects of sculpture like monuments that supposedly stand on traditional pedestals for eternity. And with ‘Three Disagreeable Objects,’ viewers could actually become participants in the composition of the sculpture by moving these objects around. And that kind of freedom in 1930 was very unusual.

He never aimed for the grand or earth-shattering.

In fact, Arp said that one of the inspirations for his thinking about making sculpture was sitting on the shore of a lake and playing with pebbles and stacking them on top of each other. And I think that sense of play, of something that can fit in your hand and has a intimate human scale was essential to his sculpture.