Roger Horchow – Mail-Order Magnate And Broadway Producer – Has Died

ArtandSeek.net May 2, 2020 10He met George Gershwin as a child and fell in love with his music. He went on to sell luxury goods by mail order like no one else — and then created one of the ultimate luxury goods: his very own George Gershwin musical on Broadway.

Roger Horchow, the Dallasite who created The Horchow Collection catalog and produced the now-classic Broadway musical, “Crazy for You,” died early Saturday after a long battle with cancer, his daughter Sally Horchow confirmed. He was 91. Sally said there would be no memorial service — as her father had stipulated.

“He wanted to be at his own funeral,” she said, “and he can’t, so we thought we’d honor his wishes.”

Service to KERA

Nico Leone, president and CEO of KERA, sent the following message to the board of KERA. Horchow was a long-time supporter of the station and had served on its board:

“Roger was a dedicated and longstanding member of our Board, most recently confirmed as an Honorary Life Director. He also was a titan in the North Texas philanthropic community who made significant investments in local institutions, including KERA, Dallas Museum of Art, UT Southwestern and many more.

“Beyond his successful career as an entrepreneur, Roger was also an award-winning Broadway producer. When he recorded a video testimonial for KERA’s major gifts program, he treated the crew to a piano performance – his Tony Award proudly displayed above the keys. It was just one of the moments with Roger that our KERA family will never forget.

“Roger’s commitment to KERA extended throughout the Horchow family. His son-in-law, Dan Routman, is a former KERA Board Chair who served alongside Roger and continues to serve as an Honorary Life Director.

On behalf of the KERA family, our thoughts are with Dan and Roger’s entire family, including his three daughters.”

A retail pioneer

Roger Horchow was the first retailer to sell high-end goods by mail-order catalog — without first opening a bricks-and-mortar store on the street to establish its reputation with buyers. He was so successful, he sold his mail-order outfit to the store that had hired him and inspired him: Neiman Marcus. Then he went on to win a Tony Award producing his very first show, which became a world-wide success. And this was when one out of every 22 Broadway shows actually made its money back.

In his one life, Roger Horchow was a pioneer in retail while being a Broadway traditionalist when it came to singing and dancing entertainment. But perhaps his real skill was not in knowing which sumptuous trinkets the affluent might buy, or even in bringing back splashy American showbiz: He was profiled in a major bestselling book by Malcolm Gladwell for the simple reason that — as most people who met Horchow realized — he had a low-key friendliness, a charming, sleepy-eyed knack for getting to know just about everyone — and remembering them.

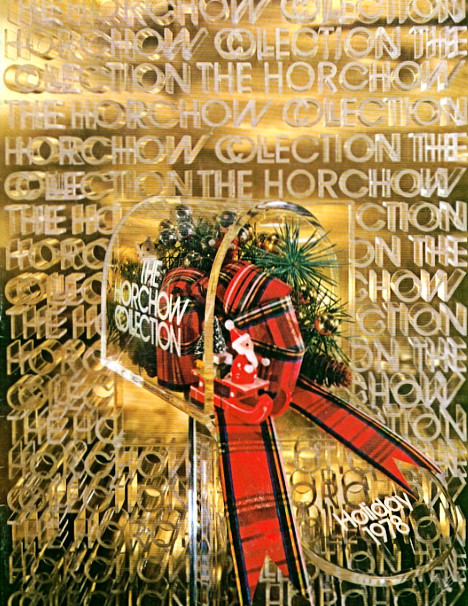

The Horchow Collection’s holiday catalog for 1978.

Samuel Roger Horchow’s father was a lawyer and a state government official. Even so, the younger Horchow was born into the retail business in Cincinnati in 1928. His Ohio family were mostly shopkeepers. His grandfather had been a pack peddler in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and eventually owned a general store in Crooksville, Ohio. Some of the largest stores in nearby Zanesville were owned by Horchow relatives, and Horchow later recalled being fascinated by Sears, Roebuck and the other mail-order catalogs of the day. They’d arrive in the post like Christmas packages to be unwrapped and pored over. He learned the personal art of sales by peddling Burpee’s flower seeds and magazine subscriptions door-to-door.

But it was while Horchow was on a summer break from majoring in sociology at Yale University that he truly found his calling, when he went to work for the Lazarus family in Columbus, Ohio. They ran a department store that eventually became Federated Department Stores, owners of Foley’s, Sanger-Harris and Macy’s. Horchow started there by ironing curtains in the basement. He eventually became Foley’s top buyer of china and glassware.

Horchow served in the Korean War in security data analysis in Massachusetts and met his wife Carolyn Pfeiffer — perhaps inevitably — in the fashion department at Bloomingdale’s in New York. The couple eventually had three daughters: Sally Horchow, Regen Horchow Fearon and Elizabeth Horchow Routman. In 1960, when he was offered a job in charge of the gift galleries at Neiman Marcus, the Horchows moved to Dallas. Roger soon became the vice-president at Neiman’s — the v.p. in charge of mail-order and catalog sales.

“He actually joined my father on a trip to Asia,” recalled Richard Marcus, son of Stanley Marcus and the former CEO of Neiman’s. “My dad had gone into China with my mother a couple years earlier. And I think the world suddenly got bigger for him [Horchow]. There was a sourcing opportunity for him, and he wanted to run his own show. And he did a good job of it.”

One source of Horchow’s impatience, says Marcus, is that Neiman’s was primarily known for its fashions — “soft goods,” in tradespeak — and Horchow saw how more could be done with home decor or “hard goods.” In 1971, after he learned he wouldn’t become head of the mail-order department quickly enough to suit him (and Neiman’s wouldn’t make their mail order business independent from the parent store), Horchow went to work for the Kenton Corporation, a conglomerate that owned some of America’s leading designer labels, including Cartier and Valentino. He started their catalog, the Kenton Collection, in May 1971. What made no sense to successful retailers at the time was Horchow’s insistence that the choice of mail-order items should include products outside the stores’ day-to-day inventory and be handled not by the store’s usual buyers. They didn’t see mail order as a potentially independent (and therefore different) market but as just another (limited) revenue opportunity for what they already peddled.

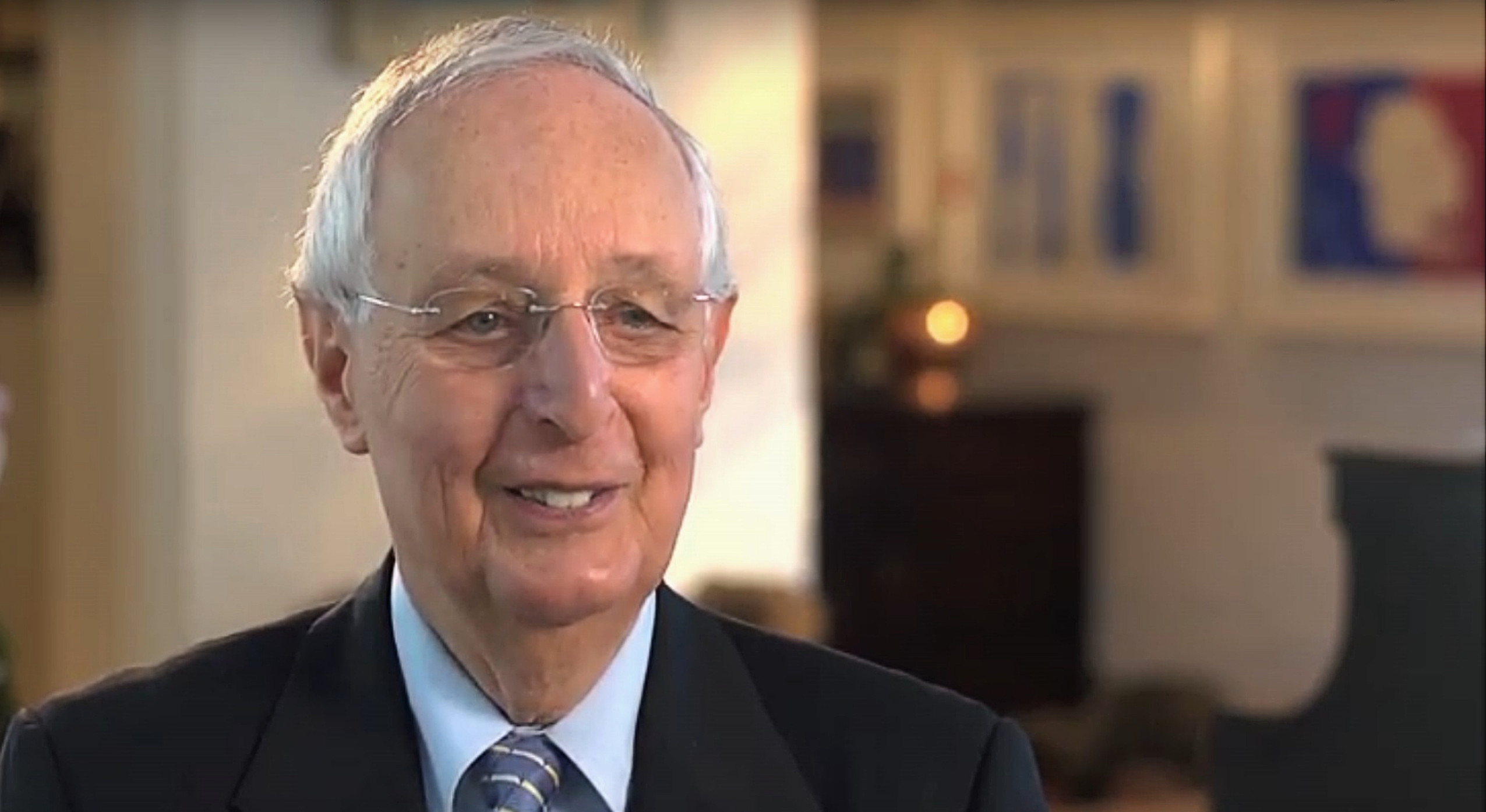

Roger Horchow in his Dallas home in 2013. Image: M3FilmsLLC

Timing is everything

Indeed, Horchow’s new Kenton Collection lost one million dollars its first year in business — as Horchow had predicted. Then it lost another million in its second year, which Horchow hadn’t predicted.

Still, Horchow was certain it would turn a profit in its third year. But the debt-ridden Kenton Corporation was bought by Rapid-American Corporation. So Horchow took the first big financial gamble in his life. He put together one million dollars — “hocking everything I could lay my hands on,” he said, borrowing from friends and family members and getting a $600,000 loan from a bank. On June 13, 1973, after signing nearly three hours’ worth of documents, he bought what Rapid-American was perfectly happy to sell him: his freedom to do what he wanted with his money-losing catalog.

In 1973 — as he would later recount in his 1980 mail-order memoir, “Elephants in Your Mailbox” (co-written with A. C. Greene) — Horchow would start the first luxury mail-order catalog that did not originate with a real, live retail outlet. The first issue received only 7,000 orders –but they were from people like Princess Grace. Horchow’s insight was that his catalog would offer both convenience and exclusivity. With the Sears catalog, you got what you could buy at any Sears. With the Horchow Collection, people couldn’t buy the fancy-schmancy items on their own — not unless they were willing to travel to meet Peruvian merchants or haggle in Irish villages known for their wool weaving. Customers of the exclusive Horchow Collection soon included Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra and Happy Rockefeller.

Before internet commerce came along and decimated a lot of mail order, Horchow’s success inspired all the freestanding, fashion-and-home-decor catalogs that soon followed: Frontgate, Levenger, Brookstone, Scully & Scully, Ballard Designs, Wisteria, Grandin Road. Horchow even created spin-offs of The Horchow Collection itself, and the whole business was so successful, he sold it all in 1988 to Neiman Marcus, just when The Horchow Collection was becoming increasingly indistinguishable from its competitors.

Six years later, the first internet sales began. By then, Horchow was a major Broadway player.

In showbiz, as in investments, timing is everything.

Roger Horchow at home, playing the family piano that George Gershwin once played.

Full circle with Gershwin

Horchow often recalled how, as a child, he was awakened one Sunday morning at his parent’s home by the sound of enticing piano music. In his pajamas, the six-year-old went downstairs to find George Gershwin playing the family piano. Horchow’s mother was a pianist, and the great composer was in Cincinnati for a concert. She learned he had some hours to kill before catching his train, so she invited him home. Hence, the impromptu morning performance. Roger Horchow eventually kept the piano in his own home for decades and although he never learned to read music, he would play Gershwin and other Broadway standards on it by ear. (The piano is reportedly bequeathed to his youngest daughter, Sally.)

By the 1980s, Horchow was already investing in Broadway shows, but in 1992, he set out to fulfill a stagestruck dream. He wanted to see a full-scale, glittery, George-and-Ira Gershwin musical — but done fresh. With permission from the Gershwin estate, he snagged several iconic tunes — like “Someone to Watch Over Me” — from other Gershwin musicals, and he hired playwright Ken Ludwig and director Mike Ockrent to update and refashion the Gershwin brothers’ original 1930 show, “Girl Crazy,” whose storyline and jokes had become dated.

The project became “Crazy for You” and with it, Horchow brought old-style, commercial American showbiz — complete with sequined chorus dancers, splashy sets and romantic leads singing infectious tunes — back to Broadway. It was shamelessly entertaining. At the time, the New York stage was dominated by somber, wannabe operas generally imported from England or France — heavyweight spectacles like “Miss Saigon” and “Phantom of the Opera.”

“Crazy for You” opened like a magnum of vintage champagne. It ran for four years on Broadway and grossed more than $92 million. It may well have started the entire ’90s genre of “revisals” – heavily re-worked classic Broadway shows such as “Chicago,” “Cabaret” and “The Most Happy Fella.” Thanks to director Ockrent and choreographer Susan Stroman, Horchow’s own vision of ten chorus dancers happily popping out of a limousine one by one — like tap-dancing clowns from a pricey clown car — that vision was realized with “I Can’t Be Bothered Now,” one of the show’s show-stopping numbers. It was featured on the Tony Awards TV presentation in 1992 (above). That was the awards show where Horchow picked up his first Tony as a producer. It also launched Stroman’s career as a leading choreographer-director.

In 1993, after bringing “Crazy for You” to Dallas to open its national tour, Horchow declared he wasn’t interested in creating another Broadway show. He was quitting while he was on top. In the following years, he oversaw other productions of “Crazy for You” (including one in Japan). But he was too old, he said, to start another show from scratch — he was 64 at the time — so Horchow planned on peacefully ignoring all the pitches for new theater projects that were piling up on his desk. He had wanted his dreamed-of Gershwin musical and he’d gotten his dreamed-of Gershwin musical.

Horchow eventually donated his Gershwin memorabilia and records and files from ‘Crazy for You’ to the Harry Ransom Center at UT-Austin

But over the next 24 years, Horchow proceeded to produce or co-produce six more Broadway shows, winning a second Tony Award in 2000, this time for best revival of a musical with the Gershwins’ “Kiss Me Kate.” The 2008 revival of “Gypsy” — for which he was a co-producer — earned him only a best revival nomination. But it starred Patti Lupone — and she won her second Tony Award in it, her first since ‘Evita,’ 28 years before (below).

In 2009, Horchow’s wife Carolyn died after a long struggle with cancer. They had been married for 49 years.

“They were both quiet,” says Kern Wildenthal, president emeritus of UTSouthwestern. “They complemented each other. But she never missed a beat. Anything going on she knew what was happening.”

Friends commented that afterwards, Roger seemed a little lost without her — and without a project to keep him focused. Her sense of style had been one of the inspirations for the Horchow Collection, and she’d gone most places with him. When “Crazy for You” was enduring its madcap, nail-biting tryout in Washington, D.C, Carolyn could be found in the theater, seated next to Roger, calmly knitting and giving him smart advice. Like her husband, she’d been extensively involved in North Texas non-profits and charities, including Meals on Wheels and UTSouthwestern. Both of the Horchows received medical care there, and Carolyn helped organize a women’s health care symposium at the Medical Center. Roger eventually donated money to have the annual, day-long event named the Carolyn P. Horchow Women’s Health Symposium. According to Wildenthal, Roger took delight in attending it.

While Roger may have been out of the creating-new-shows-from-classics business, he continued investing in other people’s musicals — including “Hamilton” and “The Book of Mormon.” But in 2018, he announced he was investing in a revival of “Crazy for You” — with its original choreographer, Susan Stroman, now slated to direct. All they needed, he said, was the right Broadway theater available for a good length of time.

But in recent years, an open Broadway stage has become an extremely rare commodity — when tourist blockbusters like “The Lion King,” “Phantom of the Opera” and “Wicked” continue to sit there, decade after a decade.

The Horchow Connection

Not surprisingly — for someone who’d been a successful author, mail-order merchant, Broadway investor, producer and philanthropist — Horchow had a knack for making friends easily. It was a skill that author Malcolm Gladwell highlighted in a feature story in “The New Yorker” in 1999. Gladwell, the author of such later bestsellers as “Blink” and “Outliers,” wrote about the kind of people who seem to know everyone — or if not, they always know someone else who knows the person in question. Horchow was a prime practitioner of friendly networking. Gladwell met Horchow through Horchow’s daughter Lizzie, who went to a school with a friend of the Canadian journalist. At the time of “The New Yorker” story — pre-Facebook, pre-Snapchat, pre-Twitter and pre-WhatsApp — Gladwell reported that Horchow had a computerized Rolodex with contact information on sixteen hundred people.

Gladwell wrote: “I kept asking him how all the connections in his life had helped him in the business world, because I thought that this particular skill had to have been cultivated for a reason. But the question seemed to puzzle him. He didn’t think of his people collection as a business strategy, or even as something deliberate. He just thought of it as something he did — as who he was.”

Horchow had what Gladwell dubbed “the Horchow Connection.” But as long ago as his 1980 memoir, “Elephants in Your Mailbox,” Horchow himself bragged about his ability to know someone, anyone, an old friend, a business associate — in just about any place on Earth. During his first buying trip to China in the early ’70s — well before America was even really trading with the People’s Republic — Horchow stayed in a Peking hotel full of nothing but Chinese sellers — and a very tiny number of Western buyers, most of them European. Horchow went up to one of the only Americans in all of Peking and said, “You’re Jonathan Sloat and we were in the class of 1950 at Yale.”

“Of course,” Sloat replied. “You’re Roger Horchow.”

Roger Horchow at home in 2018 admiring his collection of prints and posters. He once wrote one of his favorite framed items was the $1 million check he wrote to buy what became The Horchow Collection.

In 2000, “The New Yorker” profile of Horchow was featured in Gladwell’s first book of pop sociology, the bestseller that made the author famous: “The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make A Big Difference.” In 2005, Horchow and his daughter Sally turned Roger’s approach to friendliness into an advice book, “The Art of Friendship: 70 Simple Rules For Making Meaningful Connections.” It was his third book, after “Elephants in Your Mailbox’ and “Living In Style In a Time When Taste Means More Than Money” from 1981.

Horchow always spoke in a slow, gentle drawl — it suited his sleepy eyes and dry sensibility. But that speaking style did not make his audiobook recordings particularly gripping. They didn’t convey his warmth or dry humor.

Excerpt from the introduction to Horchow’s audiobook version of “The Art of Friendship”:

But in the early 1990s, Horchow found his speaking style could be a shrewd negotiating tool. At the time, he said, he was struggling to put together “Crazy for You,” and for the first time, he was wrangling with a big-time Broadway creative team over a ballooning budget. Investors in a show generally aren’t the ones to do this. It’s what producers do: bring the artistic team together and hammer out what’s going to get spent. Then they get investors to bankroll the whole package they’ve put together.

But “Crazy for You” didn’t have to wait years to rustle up backers and raise money. Broadway veteran Elizabeth Williams was officially co-producer of the show, but she was really there to advise Horchow, who basically wrote the checks. So the typically tedious investment process barely existed. They already had all the money.

And then the Shubert Theater became available.

Everything that Horchow’s team had decided they wanted had to be purchased, rented or arranged now-now-now — winches, wigs, scenery, lighting, transportation, size of orchestra — all of it in advance of the Washington, D.C,. tryout in January 1992. The New York premiere was one month later.

With such a sudden time crunch, costs went through the roof.

But eventually, Horchow said, he learned to use his sleepy voice to his advantage. During intense arguments with designers and technicians over budgets, he said he would go over each line item slowly.

“And you know, I talk pretty slow as it is,” he said.

And he’d ask more questions and get even slower.

Then his eyes would glaze over.

Eventually, everyone gave up and the costs would start to come down.