Researchers Say Better Public Spaces = Better Civic Engagement

ArtandSeek.net March 11, 2017 10Art&Seek is back in Austin at South by Southwest (SXSW) this week, and KERA’s Alan Melson is among those sharing dispatches from the annual conference of interactive, film and music. Friday, he wrote about AI and emotive design, and today he focuses on urban planning and engagement.

Despite the litany of complaints about SXSW and its effect on Austin – with throngs of visitors and countless product demos, music showcases and publicity stunts clogging the downtown streets – one reason that the conference remains a draw is the popularity of its home city. Austin has a thriving civic life, beautiful public spaces and a city government that (usually) understands the value of both.

Saturday’s “Designing for Engagement: How Smart Urban Design Can Shape Space for Civic Life” panel put forth the idea that better planning for shared public spaces can get residents more involved and more passionate about where they live – and help make their cities better. Urban planner Suzanne Nienaber joined with political strategist Kate Catherall to talk about the connection points between their respective worlds, along with George Abbott of the Knight Foundation, which funds community initiatives around growth in civic engagement, including a new project from Nienaber’s nonprofit organization.

Catherall opened the presentation with a foreboding series of statistics about growing polarization in America, which has repositioned politics as a zero-sum game that fosters divisiveness and what she termed a “rising tide of mutual antipathy and dehumanization.” This political bitterness has increased the feeling that individual voices aren’t heard or don’t matter – and voter participation has dropped as a result. This vibe permeated the 2016 election cycle, and shows little sign of abating amid the political uncertainty of a new presidential administration.

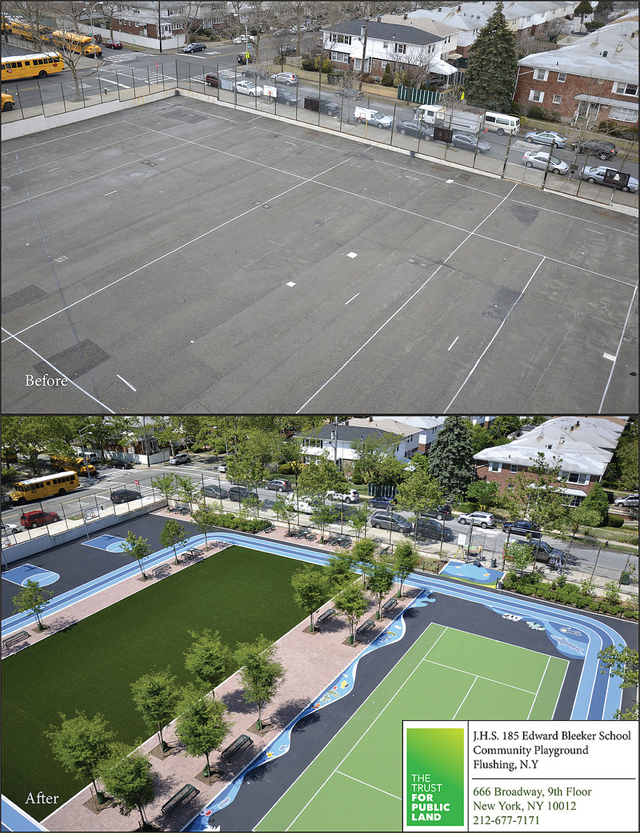

Given all that, how can we build community relationships and look for commonalities? Nienaber believes the transformation of our physical environment is at least part of the answer. Her New York-based nonprofit Center for Active Design bases its work on the concept that changing the design and development patterns of a community has a direct impact on people’s health and behavior. She referenced several examples, from the conversion of a school’s asphalt lot into an inviting natural playground, to the careful design of a community master plan in Seattle – both projects that emphasized welcoming, open elements and utilized community input to shape the design.

A New York City playground was reimagined from a cold asphalt pad to a welcoming new play space with natural elements. (New York Department of Environmental Protection)

Her group does extensive research, analyzing existing resources and data sets, identifying gaps and formulating strategies to improve public spaces before beginning the actual design and implementation process. They work with communities to eliminate signs of disorder – abandoned lots, derelict buildings, evidence of crime – and emphasize walkability, accessibility, natural and green elements and gathering places that tend to become a focal point for public use.

The Center for Active Design’s new Knight-funded project, Assembly, is trying to build a framework for cities to follow. The project has four objectives: grow civic trust and appreciation, expand participation in public life, encourage stewardship of the public realm and increase informed local voting to shape future policies around growth and urban planning.

The Assembly group did a deep analysis on previous surveys around community life conducted by Gallup and others, and has done some of its own research into how residents perceive their own city’s public spaces. Not surprisingly, four independent variables stood out in the data as having a strong association with civic engagement:

- Availability of outdoor recreation space

- Perceived community beauty

- Access to arts and culture

- Availability of community events

The research team did several experiments, including one where they provided three examples of vacant lots with increasing levels of maintenance and asked people to imagine each near their home. The well-maintained, community-garden style lot led to 48 percent of respondents reporting it indicated a high level of pride in the community, versus only 8 percent for an un-maintained vacant lot.

Nienaber also stressed that it’s important to avoid associating improvement of public space only with high-income or gentrifying areas.

“When you have urban neighborhoods with systematic disinvestment, it is imperative for cities to use funds to apply to libraries, public playgrounds, parks and other community spaces of greatest need,” she said. “Everyone deserves the right to have positive public amenities. They should not be associated with privilege.”

These projects don’t have to be confined to truly urban environments, either. Suburbs can do a lot both through high-level master planning as well as by simply building in funds to redesign, maintain and upgrade existing public spaces.

“Some of the most fascinating results out of recent surveys were the fact that the condition of public space amenities is equally, if not more, important for promoting civic trust,” she said. “It’s not just that you have a park, but is that park clean? Is the playground in good condition?”

Catherall said public buy-in for such projects leads to more engagement in local politics in a positive way – and she feels that is now happening in a much more authentic way at the local grass-roots level than in statehouses or federal buildings.